Key Takeaways

- The Chelsea Hotel in Manhattan has a rich history as a haven for cultural icons like Mark Twain, Bob Dylan, Patti Smith and more.

- Originally designed as an affordable artist's co-operative, the hotel has been a hub for collaboration and creativity for over a century.

- Despite its ups and downs, the Chelsea remains a legendary place where artists, celebrities and dreamers have found inspiration and community.

The scaffolding of a stalled renovation project has hidden the façade of the Hotel Chelsea in Manhattan for years now. But no amount of dust could obscure the hotel's lustrous history – because "the Chelsea," as it's often called, has been a home to a veritable encyclopedia of cultural icons..

Mark Twain, Stanley Kubrick, Arthur Miller, Jack Kerouac, Bob Dylan, Leonard Cohen, Nico, Patti Smith, Sam Shepard, Mitch Hedberg, Charles R. Jackson, and Dennis Hopper, among many others, all stayed there at one time or another. Some for a short time, others for years. Robert Mapplethorpe, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Dee Dee Ramone – the list of stars goes on and on.

Advertisement

Of the Chelsea, Patti Smith wrote in her memoir "Just Kids," "I loved this place, its shabby elegance, and the history it held so possessively."

But what is it about this hotel – of all the hotels in New York City – that gives it so much gravitational pull for artists of all kinds?

Turns out, it was designed for exactly this purpose.

"It was initially built by Philip Hubert as an affordable artist's co-operative (though it was quickly taken over by upper and middle-class New Yorkers) and only later reopened as a hotel," emails Nicolaia Rips, an author who wrote about her experiences of growing up in the hotel in the 2000s. "If you believe that you imbue the things you create with purpose, which I do, then it is very simple: art is in the hotel's foundation, it is as essential to the hotel as the brick and mortar."

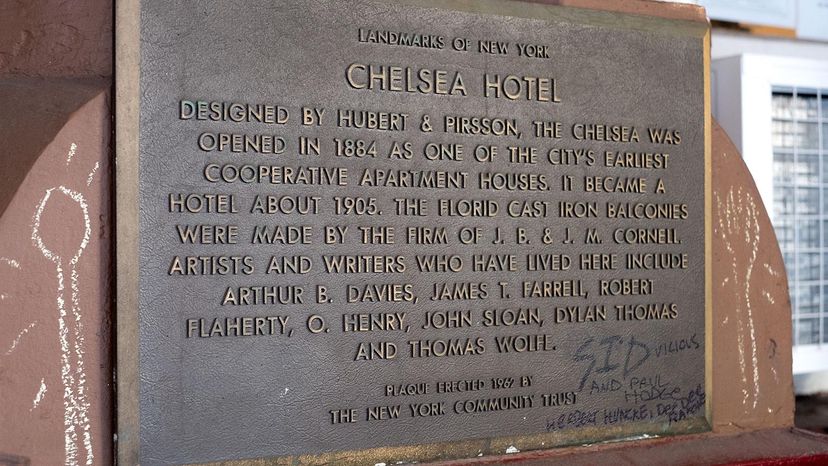

It was Hubert, a founder of the architectural firm of Hubert, Pirsson & Company, who brought the Chelsea to life in the mid-1880s. He was an avid follower of Charles Fourier, a French philosopher who imagined various forms of utopian socialism. More specifically, Fourier was a steadfast proponent of so-called "intentional communities," in which teamwork and shared social values are top priorities.

In designing and building the Hotel Chelsea, Hubert wanted just that – a place where people from varied backgrounds and lifestyles would feel safe in sharing their lives in the spirit of collaboration.

"To my knowledge, it's the largest and longest-lived artists' community in the history of the world," says Sherill Tippins, author of, "Inside the Dream Palace: The Life and Times of New York's Legendary Chelsea Hotel."

This vision was a grand success, as evidenced by the incredible number and variety of people who've called the Chelsea home at one time or another. And although the hotel is famous for its celebrities, regular types live there, too.

"The mix of types of residents provides fodder for art – the doddering old ladies with their shocking stories from their pasts, the lonely heiresses who come to take their lives there, the high-fashion models struggling to manage their professional lives, the deli workers and taxi drivers and drug dealers – all mingling, conversing, and sharing their lives in the lobbies and elevators, in the roof gardens and at El Quijote next door," says Tippins. "Together, they comprise a human tapestry mirrored in paintings, songs, dances, compositions, sculpture, photographs, and stories and novels that have been created there."

You may wonder how artists of varying success – who are not always known for timely paychecks – managed to score rooms at a famous hotel in downtown New York City.

Tippins explains that historically, for many, the hotel was purposely made affordable because the Bard family, who managed the hotel from the 1930s through early 2000s, recognized the value of having well-known visitors or residents in the hotel. The Bards were willing to discount rent (or even forego rent or accept artworks in lieu of cash) to help artists make their way.

"During these years, the hotel grew increasingly run-down, which was fine with most residents since that meant the rent could not be raised too drastically, either – the fortunate trade-off that anyone who's lived in rent-stabilized housing in NYC understands," says Tippins.

She also points out that it's remarkable how, over its 130-plus history, the Chelsea became a reflection of the state of the larger world. For example, when the Great Depression struck, the hotel was threadbare and lost much of its sheen. Then, in the 1960s and 70s, emergent drug culture and a plethora of social stressors and financial problems took a toll. More recently, she says, greed-fueled real estate transactions filled the pockets of investors while causing untold heartache for residents.

Advertisement