There are currently 574 federally recognized Indian nations (also known as tribes, bands, communities and by other terms) in the U.S. according to the National Congress of American Indians. About 229 are located in Alaska and the rest are in 35 other states. Of that number, five were called the "Five Civilized Tribes," a term which didn't save them from being forcibly removed to "Indian Territory," in the 19th century. So, where did that term come from and who were they?

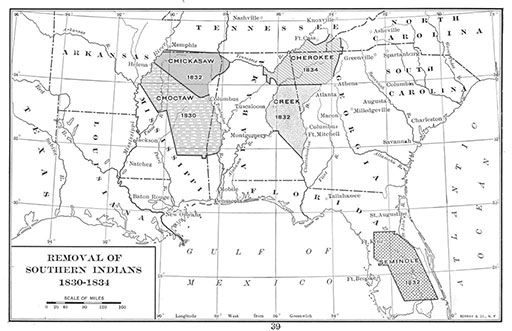

By the time the first European settlers arrived in America, there were already more than two dozen Native American tribes living in and farming the fertile soil of the Southeast, in the area today encompassing the states of North Carolina down through Georgia, Florida and the Gulf Coast. Like other Native peoples who came in contact with Europeans, these Southeastern tribes were ravaged by diseases like smallpox. Over time, they learned to adapt to the encroaching white culture in ways that they believed would secure their survival and sovereignty.

Advertisement

Many members of these Southeastern tribes converted to Christianity, for example. They took to wearing European-style clothing and living in frame houses. They adopted the agricultural practices of their Southern white neighbors, including ownership of enslaved people, and sold goods in a market economy. They intermarried with whites, spoke English, and sent their kids to schools run by Christian missionaries.

As a result, by 1800, five of the largest Southeastern tribes were routinely referred to by U.S. government officials as "civilized," explains Andrew Frank, a scholar of Indigenous and Seminole history at Florida State University.

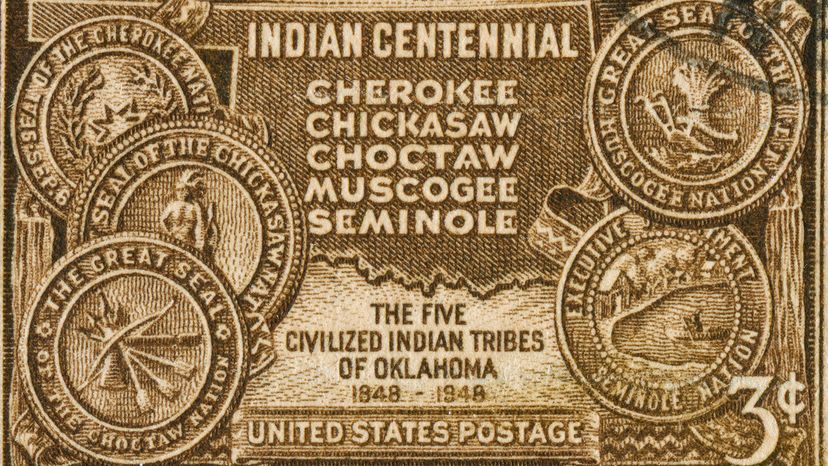

"American officials drew a distinction between these five tribes — the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek and somewhat the Seminole — and what they would call the 'wild, wandering and uncivilized' tribes elsewhere," says Frank.

The Cherokee were the largest of the "civilized" tribes. By 1830, they had a written constitution with a democratically elected assembly and chief, and they published a newspaper in both Cherokee and English.

"Among Southern whites, those earmarks of 'civilization' suggested that there was a willing assimilation into American culture," says Mark Hirsch, an historian with the Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of the American Indian.

But Frank says that appearances can be deceiving. If you look back deeper into Native American history, Native peoples always incorporated new technologies and customs from their neighbors. And when circumstances in their environment changed — a drop in wild deer population or the introduction of maize — the people changed with them.

"But in almost every instance, the adoption of these new outside things was done for the purpose of protecting Indigenous people, not abandoning them," says Frank. "Despite the appearance of 'civilized' customs, Native people had no interest in becoming part of the United States. They had no interest in assimilating into a white norm. How better to resist the oppressors than to learn their language?"

Advertisement