In the early 2000s, two economic researchers conducted a simple yet revealing experiment. They submitted nearly 5,000 fictitious resumés to "help wanted" ads posted in Chicago and Boston newspapers. The jobs were for entry-level positions in sales, administrative support, clerical and customer service.

The resumés were all nearly identical — same levels of education, work experience, etc. — except for one difference: Half of the job applicants were given stereotypically Black names like Lakisha and Jamal, while the other half were given "whiter-sounding" names like Emily and Greg.

Advertisement

The result? Resumés with white-sounding names received 50 percent more callbacks for interviews than resumés with Black names. In a separate experiment, even white job applicants with criminal records received more callbacks (17 percent) for the same jobs than Black applicants with no criminal record (14 percent).

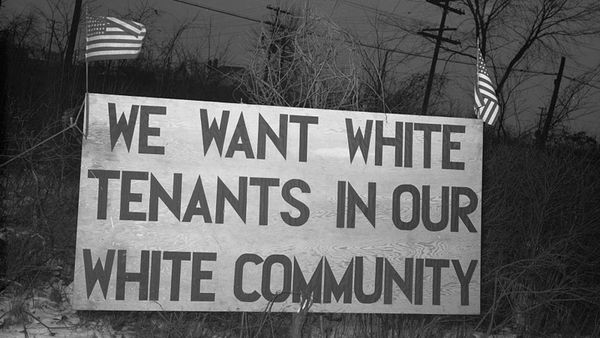

So, what exactly is going on here? Is it that the hiring managers at hundreds of different companies were all avowed racists or card-carrying white supremacists? Not likely. In the case of the second experiment, in which white and Black job applicants applied in person, the researchers wrote that "few interactions between our testers and employers revealed signs of racial animus or hostility toward minority applicants."

The employers were not outwardly racist, yet the outcomes differed significantly across racial lines. Studies like these and others shine light on what's called "systemic racism," a type of baked-in racial bias that overwhelmingly benefits white Americans while disadvantaging Americans of color.

Advertisement