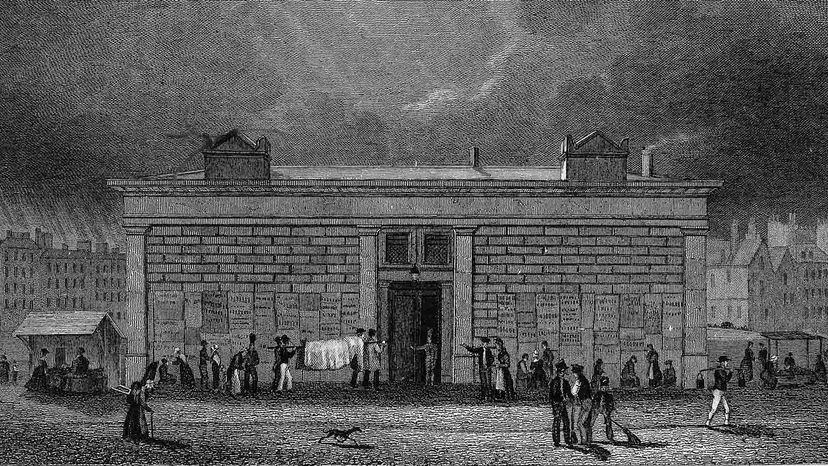

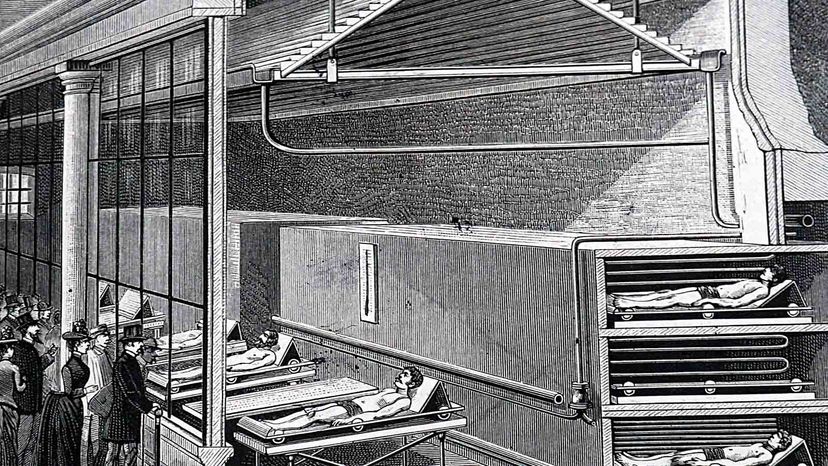

In 1864, a wildly popular new type of "theater" opened in Paris. It was free and open seven days a week. Street vendors sold fruit and nuts to the long line of curious tourists and passersby that waited outside to see the show. Once inside the darkened and hushed exhibition hall, attendants drew back the curtains to display a remarkable scene: corpses.

This was just another day at the Paris morgue.

Advertisement

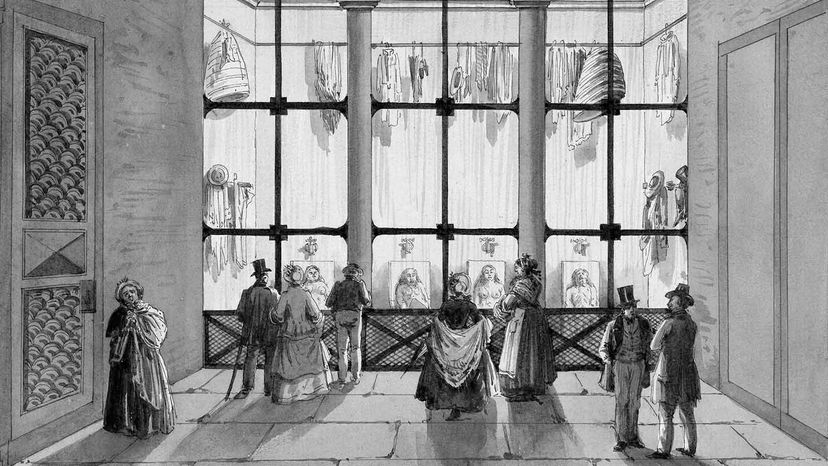

As macabre and downright creepy as it sounds, the morgue was one of the most popular sights in Paris in the late 19th century. As many as 40,000 people a day would file through the morgue's salle d'exposition to gawk at the half-naked, decaying corpses — many of them freshly fished from the nearby river Seine — laid out on marble slabs behind a plate glass viewing window. It was even listed in British tour books as Le Musée de la Mort.

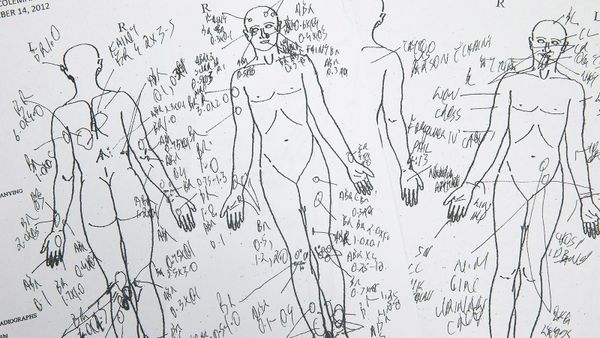

The official purpose of the Paris morgue's exhibition hall was to recruit the public in the somber task of identifying the city's unclaimed and unnamed dead. "But of course it was also a show," says Vanessa Schwartz, a professor at the University of Southern California and author of "Spectacular Realities: Early Mass Culture in Fin-de-Siecle Paris."

Schwartz makes a convincing argument that the Paris morgue — along with the city's wax museums and sensationalist newspapers — combined to create a type of Gilded Age "reality TV" or "true crime" show, and the audience couldn't get enough of it.

Advertisement