In a small town in Normandy, France, admiration for handcrafting has never gone out of style. Known since the 17th century for its fine lacemaking tradition, Alençon, France, is still home to the nationally sponsored Atelier Conservatoire National du Point d'Alençon (National Alençon Lace Workshop). It's where artisans learn to make the delicate point d'Alençon lace, regarded as the "queen of laces" and the historical favorite of queens like Marie Antoinette.

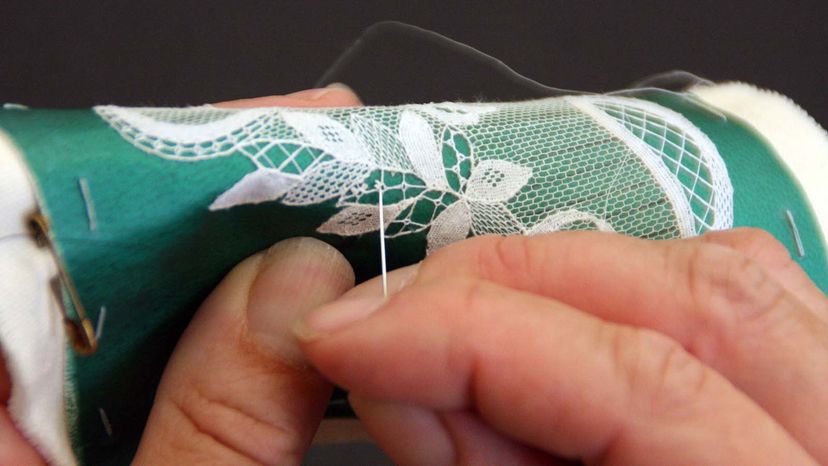

The importance and rarity of point d'Alençon — also known as Alençon needlepoint lace — is due to the fact that it is made entirely by hand with needles, thread and parchment, just as it has been for more than 350 years, explains Valérie Durand in an email translated from French. Durand joined the National Alençon Lace Workshop in 2006 and is now its head. She was named "One of the Best Workers in France" by the COET-MOF for needle option lace in 2019 for a Point d'Alençon bracelet she crafted.

Advertisement

Today's Alençon lacemakers like Durand learn the process during an apprenticeship that can last up to a decade. And while other lace may claim to be Alençon, the authentic stuff, which bears the name of the city where it was born and perfected through thousands of Normandy lacemakers, is as inseparable from its place of origin as from its technique, she says. But interestingly, the story of this famed French lace begins somewhere else.