"[Huey Newton said], 'You know, the nature of a panther — I looked it up... If you push it into a corner that panther is going to try to move left or right to get you to get out of the way. But if you keep pushing it back into that corner sooner or later that panther is going to come out of that corner and try to wipe out who keeps oppressing it in that corner.' I says, 'Wow, Huey, That's just like black people — we're pushed in a corner.'"

That's how Black Panther co-founder Bobby Seale described how the Black Panther Party got its name [source: Oakland Museum of California].

Advertisement

The Black Panther Party was founded in 1966 by Merritt College students Bobby Seale and Huey Newton in Oakland, California [source: Duncan]. The pair was frustrated by persisting racial inequalities in police treatment, housing, education, health care and other fundamental areas.

But a big part of their platform was self-defense — defending themselves (and other African Americans) from the police and other people who might want to hurt them. Newton and Seale thought the non-violent civil rights movement championed by Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. was moving too slowly, and they identified instead with the more radical ideologies put forth by leaders like Malcolm X. Indeed, the original name of the group was the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense [source: Oakland Museum of California].

The organization eventually spread to chapters in 48 states and a number of other countries, including South Africa, Japan and England [source: Duncan].

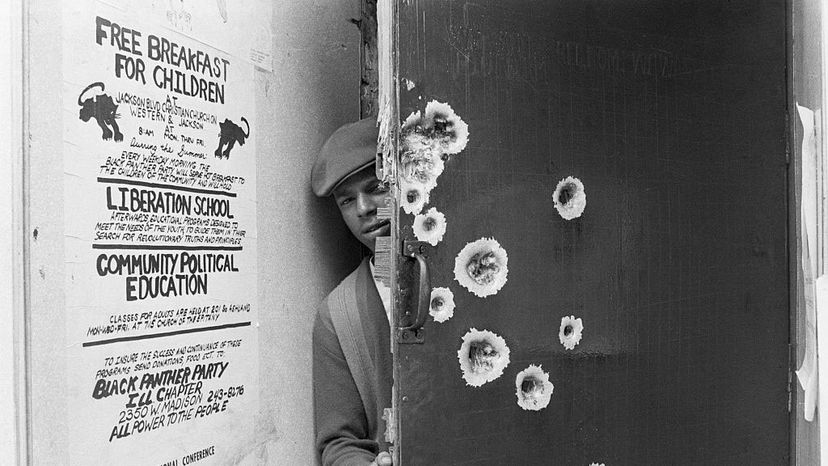

Party leaders developed a specific Ten Point Program that outlined the organization's concerns and demands. Equal opportunity for employment at a fair wage, financial reparations for the enslavement of millions of African Americans, and access to decent housing, education and health care were among the issues listed. They also called for the release of Black and oppressed prison inmates because, in the words of the program manifesto, "We believe that the many Black and poor oppressed people now held in United States prisons and jails have not received fair and impartial trials under a racist and fascist judicial system and should be free from incarceration."

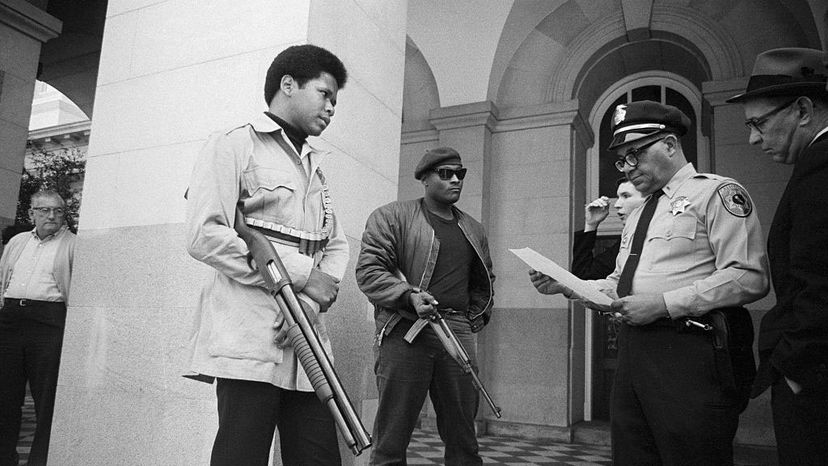

The party began to elicit attention by conducting armed patrols of Oakland's poor neighborhoods, which was perfectly legal thanks to a loophole Newton discovered in state law that permitted loaded weapons to be carried openly. So, Panthers walked the streets, witnessing arrests and other police interactions in an effort to discourage brutality [source: Blake]. Not surprisingly, this tactic inspired fearful politicians to change the law, post haste, all the while driving more attention to the Panthers and their cause.

Advertisement