An unsolved mystery can drive people crazy, and the fate of the first English settlers ever to establish a colony in the New World is a puzzle that — let's face it — will probably never be entirely solved. But that doesn't keep people from trying.

In July of 1587, a ship carrying 90 men, 17 women and 11 children landed on Roanoke Island on the outer banks of modern-day North Carolina. The 15 men who had volunteered to stay and hold down the fort at the site when it was discovered the year before were nowhere to be found, so the 118 colonists disembarked and set about carving a colony out of the wilderness. There was much excitement when Eleanor Dare, the daughter of leader John White, gave birth to the first English baby born in the New World, and named her Virginia.

Advertisement

After a time, John White left the settlers to return to England, telling them he'd be back within the year with fresh supplies. However, England's war with Spain slowed the process considerably, and nobody was able to check on the settlement again until 1590. When White returned, his daughter, granddaughter and everyone else was gone. They had dismantled the buildings, carved the word "Croatoan," the name of the friendly tribe on a nearby island, into a tree, and vanished. There was no sign of the cross White told them to carve on a tree if they left under duress.

Frankly, White didn't look very hard for his daughter and granddaughter before heading back to England. For centuries, the story of the Lost Colony of Roanoke seemed pretty cut and dried to most historians: The settlers went to live with the Croatoan tribe — whether they stayed there or not, nobody could say. The thing they could say is that, despite rumors in the later-established Jamestown colony of massacres and men wearing European clothes deep in the wilderness, no definitive sign of any of the 118 castaways was ever found.

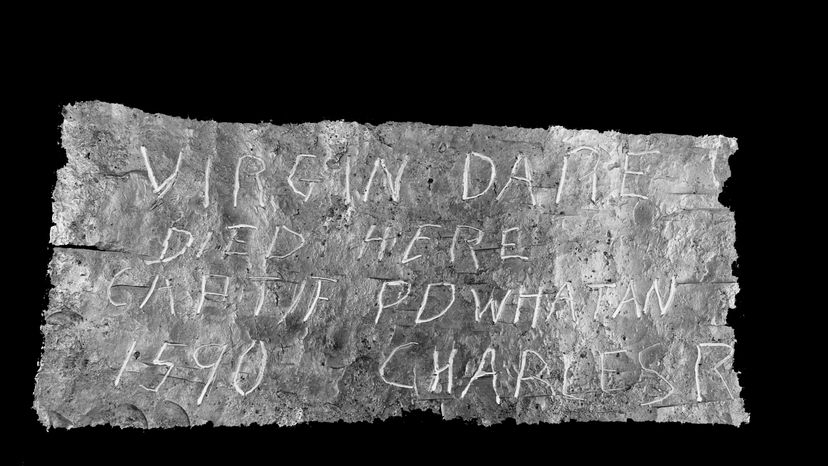

That is, until about 350 years later, when, in 1937, a produce dealer from California named L.E. Hammond showed up at Emory University in Atlanta with a stone he found while hunting hickory nuts in a recently cleared North Carolina swamp, some 50 miles (80 kilometers) inland of Roanoke Island. It was inscribed with a message he wanted the experts at Emory to decipher. Turns out, the carved stone told a story, allegedly written by White's daughter Eleanor: The colonists endured two years of "Onlie Misarie & Warre," after her father left for England, ending with half the settlers killed in armed combat and many of the others, including Eleanor's husband and daughter, slaughtered when a shaman of the tribe they lived with warned that the presence of the English settlers was angering the spirits. According to the stone, only six men and a woman escaped.

The stone was found to be authentic by the Emory experts — it seemed legitimate, and, better still, it satisfied everyone's thirst for closure around this dusty old riddle. The story captured the imagination of the entire country, and Emory professor Haywood J. Pearce Jr. published a paper describing the stone in the reputable Journal of Southern History in 1938. But soon, the plausibility of the stone came into question.

"Emory became suspicious of Hammond after some professors and administrators traveled with him to Edenton, North Carolina where he found the stone," says John Bence, archivist at the Rose Library at Emory University. "The search for the original location of the stone was fruitless; this added to the growing list of details about Hammond's discovery that were hard to corroborate. Emory had someone in California look into Hammond but couldn't find much more than an address."

After Pearce and his father, Haywood J. Pearce Sr. (who owned the private Brenau College — now Brenau University — in Gainesville, Georgia), paid Hammond for the first stone and offered a $500 reward for any additional stones people might find, you can imagine how many Dare stones came out of the woodwork. The Pearces paid a man named Bill Eberhardt, a stone cutter from Fulton County, Georgia, $2,000 for 42 forgeries he brought them. These stones had Eleanor marrying a Cherokee chief, giving birth to another daughter named Agnes and eventually dying in a cave in Georgia.

In April 1941, the Saturday Evening Post ran an exposé on the Dare stones, dismissing them all as forgaries, citing anachronistic language and a consistency of spelling unheard of at the time. Pearce's career suffered, and the Dare stones were stuffed in a Brenau University basement, an embarrassment to everyone involved.

But every so often, academic interest turns again to the Chowan River stone — the original Dare stone, found by Hammond in that North Carolina swamp. It is made of different rock than the others — a bright white quartzite interior and dark exterior would have made a good choice for Eleanor Dare's missive to her father, and in the 1930s the patina on the stone would have been difficult to chemically replicate. In addition, it doesn't contain the anachronistic language of the other stones — some experts have determined the only problem might be in Eleanor Dare's signoff, the initials EWD, which would not have been a typical signature in the 16th century.

Many experts still dismiss the Chowan River stone as an obvious phony, but it's possible new technologies in Elizabethan epigraphy, chemical analysis and other rock inscriptions of the time period can shed light on this still-unsolved mystery.

Learn more about the Dare stones in "The Lost Rocks: The Dare Stones and the Unsolved Mystery of Sir Walter Raleigh's Lost Colony" by David La Vere. HowStuffWorks picks related titles based on books we think you'll like. Should you choose to buy one, we'll receive a portion of the sale.

Advertisement