It may seem like a given that when Americans call for an ambulance, a trained paramedic will be on board the truck to begin administering emergency care. But as recently as 50 years ago, this was not the case — ambulances were more like taxis to the nearest hospital. That all changed thanks to an ambulance crew recruited from a poverty-stricken black neighborhood in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, that operated between 1967 and 1975. They became the very first ambulance workers in the U.S. trained in advanced life support, setting the bar for generations of emergency medical technicians (EMTs).

If you had a heart attack in 1960s-era Pittsburgh, you had two choices: call the police or a private ambulance company. The police would arrive in a paddy wagon — the same one used to transport criminals, equipped with a canvas stretcher and maybe an oxygen bottle — toss you in the back and roll you to the hospital. Private ambulances were oversized Cadillacs mostly owned by funeral homes (not a good omen), and drivers had no medical training.

Advertisement

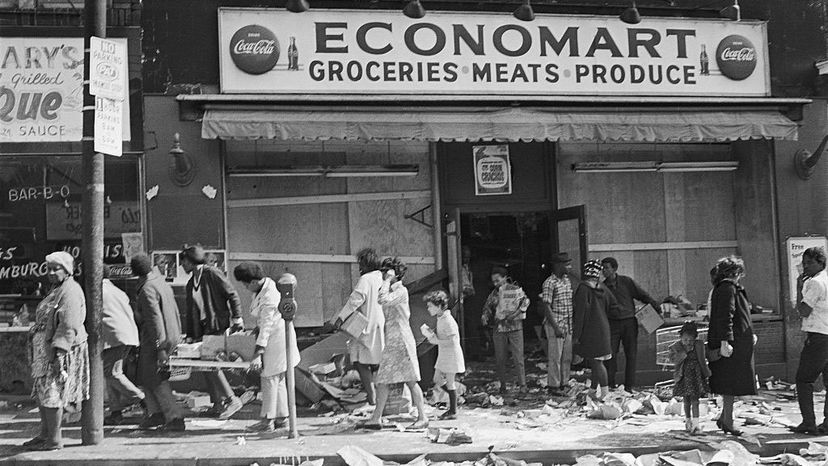

For the residents of Pittsburgh's Hill District, an historically black community ravaged by drugs, crime and economic neglect, an emergency call to either the police or a private ambulance company might go unanswered, or else the vehicle would arrive only in time to ship the body to the morgue.

That changed in 1967 when Freedom House Enterprises opened its doors in the Hill District as a community empowerment agency focusing on employment and voting rights. At the very same time, a social reformer named Phil Hallen, disgusted that the Hill District had no reliable ambulance service, dreamed up the idea of training local men — many of whom were labeled as "unemployable" — to provide emergency medical response in the community.

Hallen found the perfect partner in Freedom House, but the project would never have succeeded without Dr. Peter Safar at Pittsburgh's Presbyterian-University Hospital. Dr. Safar, an Austrian-born anesthesiologist, had single-handedly pioneered the practice of CPR and was a vocal advocate for bringing life-saving medical techniques like CPR out of the hospital and into the streets.

With Safar's expertise, and initial funding provided by the city, nonprofit foundations and President Lyndon Johnson's "War on Poverty," the Freedom House Ambulance Service was born on April 15, 1967.

Advertisement