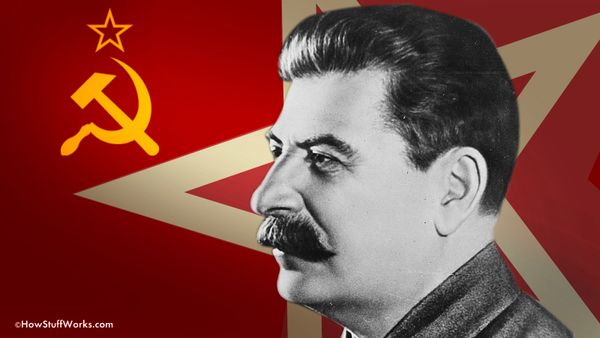

As the world watches Russian leader Vladimir Putin's barbaric attempt to conquer Ukraine, a roughly Texas-sized nation along the Black Sea to the west of Russia, many are not aware of another brutal crime against Ukraine that happened roughly 90 years ago. Known as the Holodomor, a term derived from the Ukrainian words for hunger ("holod") and extermination ("mor"), it was a time from 1932 to 1933 when millions of Ukrainians were starved to death by the regime of Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin, a figure for whom Putin has expressed admiration.

"The Holodomor was a consequence of Stalin's forced collectivization policy, which was launched in 1929 with the aim of revolutionizing the countryside to convert it to what was perceived to be a better form of agriculture," according to Stephen Norris, a professor of history and director of the Havighurst Center for Russian and Post-Soviet Studies at Miami University in Oxford, Ohio. Ukraine was seen as a place where that goal could be accomplished quickly. And to further communist ideology, Stalin's policy also aimed to eliminate "kulaks," the class of well-to-do peasant farmers that the Soviet regime saw as enemies of the people.

Advertisement

But collective farming didn't work out well, and combined with bad weather, harvests suffered and famine began spreading across the Soviet Union in the early 1930s. But the Ukrainians, who had sought unsuccessfully to become independent after the collapse of the Russian empire before being taken over by the Bolsheviks and absorbed into the USSR in 1922, bore the brunt of the resulting famine. Stalin's regime used the famine as an opportunity to punish them. In December 1932, the regime ordered Communist party officials in Ukraine to produce more food for the rest of the USSR, even if they had to take it by force from farmers.

Teams of crop-confiscating thugs were sent to roam through Ukraine and take all the grain, vegetables, and even farm animals they could find, as this report on the Holodomor compiled by a U.S. congressional commission in 1988 lays out in grisly detail. They went into farmers' homes and tore apart their stoves and even dug into the floors and surrounding outside grounds to make sure they weren't holding back anything. Anyone who was caught hiding food, or stealing it, was severely punished. Even taking a few beets from a collective farm could earn a person a seven-year prison sentence. Two young boys were beaten and suffocated for the crime of hiding fish and frogs they had caught. At the same time, Ukraine's borders were sealed to keep Ukrainians from fleeing in search of food.

As survivors recalled in testimony to the commission, people grew so desperate that they ate leaves, weeds, old potato and beet peelings, and even killed and ate dogs and cats. Emaciated people who had grown too weak to move died in their homes and collapsed in the streets.

The commission report concluded that Stalin and his inner circle knew the suffering that his government's policies were causing. It didn't matter. "Crushing the Ukrainian peasantry made it possible for Stalin to curtail Ukrainian national self-assertion," the commission report noted.

According to Norris, the Stalin regime's decree also contained other measures to subjugate Ukraine, such as ordering local officials to stop using the Ukrainian language, so that "the crisis of collectivization became specifically directed at Ukrainians and at Ukrainian nationhood."

Advertisement