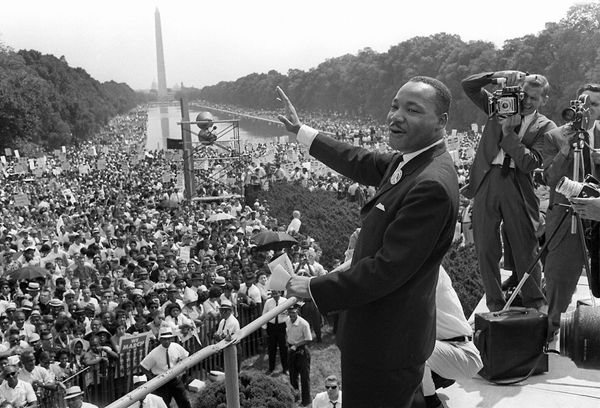

The National Mall is packed with people, most wearing dresses or slacks and ties despite the late-summer heat. For hours, passionate, heartfelt songs and speeches fill the air. Then, finally, those unforgettable words ring out: "I have a dream ... "

These are the images many of us have of the 1963 March on Washington, whether we were alive at the time or not. The most vivid is that of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.'s "I Have a Dream" speech. But King's speech, while well received, wasn't an immediate sensation. Nor was the march only about civil rights [source: Erickson].

Advertisement

The 1963 event was officially dubbed the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Its main aims were racial equality and full employment for blacks and whites. Unemployment was rising then, especially among minorities. And although there had been several major pushes for equal rights over the last decade, little progress had been made. By 1962, civil rights legislation (to prohibit discrimination on the basis of race, color, creed, religion or sex) was stalled in Congress, and U.S. President John F. Kennedy was unwilling to lend any help [sources: Erickson, Penrice].

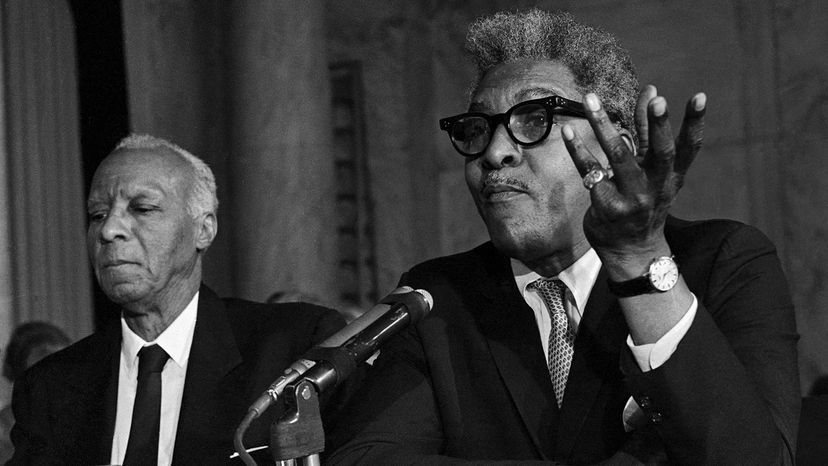

Frustrated, civil rights activist A. Philip Randolph proposed a march on Washington to demand equal rights and jobs for all. But the response from mainstream civil rights organizations was tepid [source: Penrice]. Then King signed on. Suddenly, the idea began to pick up steam. Civil rights groups that often disagreed with each other banded together -- the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), the National Urban League, the Conference of Racial Equality (CORE), the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and King's Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC).

In June 1963, a date was set: Aug. 28, 1963. The buzz was 100,000 would attend, mainly blacks. Many people became unnerved. Mainstream media wondered if the march would devolve into a riot. President Kennedy asked organizers to call off the march, but they refused. So to help ensure public safety, liquor stores and bars were shuttered that day. Stores hid or moved their valuable items. Federal employees were given the day off. And innumerable military personnel were on standby [source: Penrice].

Roughly 250,000 crammed into the National Mall. Most were black, but 10 to 20 percent were white [source: Erickson]. The group peacefully walked down Constitution and Independence avenues, then gathered at the Lincoln Memorial to hear speeches, songs and prayers. After King's speech -- the final event -- organizers and civil rights leaders met with President Kennedy and Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson in the White House. In 1964, Congress passed the Civil Rights Act, followed by the Voting Rights Acts of 1965 [source: Hendrix].

The Civil Rights Act desegregated public schools and public accommodations like hotels and theaters, outlawed discrimination in hiring and prohibited unequal application of voter registration requirements. The Voting Rights Act barred state and local governments from imposing any qualifications to voting (for instance, literacy tests) or denying anyone the right to vote because of race [source: Our Documents]. The March on Washington is credited with helping get these acts passed, though the process was not smooth sailing.

And coordinating the massive, multifaceted march took the talents of two unsung heroes.

Advertisement