Let's travel to the Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument. These 370,000 square nautical miles (490,000 square miles) of protected islands and waters stretch from Wake Atoll in the northwest to Jarvis Island in the southeast. In this cluster of small islands, you might find the sooty tern nesting in Jarvis Island, the wandering tattler browsing around Palmyra Atoll and brown boobies roosting on Kingman Reef.

All of those birds mean you're going to see a lot of something else — bird droppings.

Advertisement

Brace yourself for a little history lesson that might make you take a real interest in what islands have birds, and thus bird droppings. That is, if you're interested in claiming an imperialist stake in deserted islands and declaring them under vague, if legal, American ownership. All because of a pile of poop.

Let's start not too far in the past. In 2014, Secretary of State John Kerry and the Obama administration decided to expand the Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument from a respectable 86,888 square miles (225,039 square kilometers) to over 490,000 square miles (nearly 1.3 million square kilometers). That also meant banning commercial fishing, drilling and other disruptive activities in what became the world's largest marine sanctuary. But where did the United States get the authority to protect those islands — and their surrounding waters?

Bird poop.

More specifically, the Guano Islands Act of 1856, which essentially says that if a U.S. citizen finds a pile of guano on any rock, island or key and that location isn't already under possession of a government, you can consider it "as appertaining to the United States." (We'll get to "appertaining" later.)

This law didn't get on the books as a joke. In fact, it was a real crisis that caused lawmakers to take deposits of bird doo seriously. In the early 19th century, seabird droppings were all the craze in farming fertilizer, thanks to those droppings being super rich in phosphorus and nitrogen. Things got so wild there was even fake guano on the market, said Columbia law professor Christina Duffy Burnett, in an interview with Cabinet magazine. U.S. farmers really wanted to get their hands on the stuff, and the Peruvians, which had controlled the market, Burnett said, were running out of it.

So U.S. lawmakers created this nebulous act that says should you find guano on any unclaimed land, the United States can decide it's theirs for the taking. But it doesn't say what "appertaining" really means. It doesn't mean the guano-rich unclaimed land becomes part of the U.S. exactly. It just means, essentially, that the U.S. can use these islands or keys or rocks for collecting guano. And then they can get the heck out, for good measure.

In other words, what some argue is one of the earliest legal structures of American imperialism appears to be based on excrement.

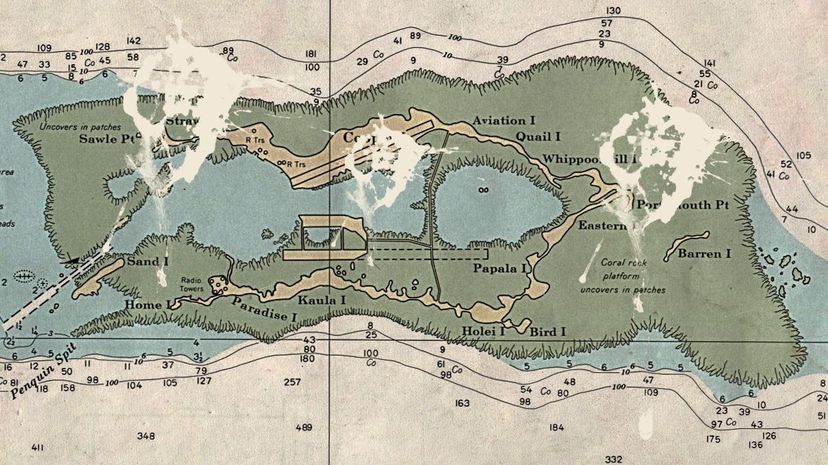

And remember, the law is still on the books today. Five of the islands (including Palmyra Atoll) that the George W. Bush and Obama administrations included in the Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument were the United States to protect only because the country was desperate for the bird poop on them, and created a rather shady way to get at it. In total, about 70 islands were claimed based on the law. And while most of the islands remain formally unincorporated, Palmyra is technically an unorganized, incorporated territory, meaning . . . well, not much. Both the Nature Conservancy and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service are now stewards of the atoll. You can check out the unique, remote spot in the Nature Conservancy video below:

Can't get enough guano? The Smithsonian's National Museum of American History had an entire exhibition devoted to the topic. The exhibition's now closed, but you can visit its digital counterpart online.

Advertisement