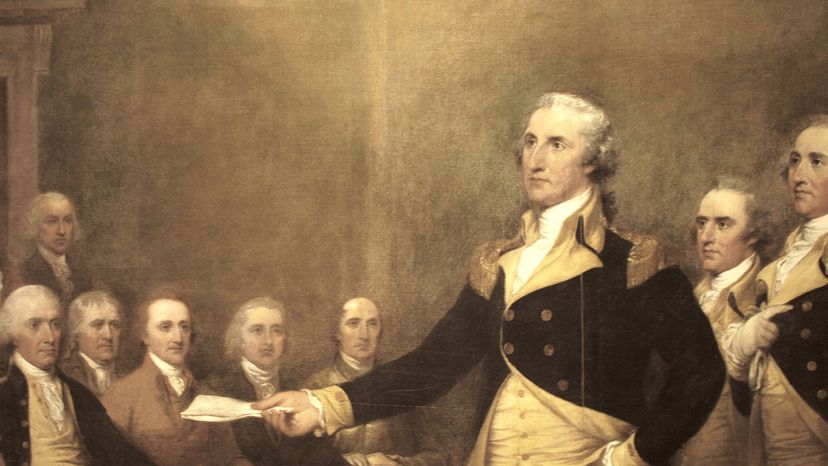

There's a popular yarn among American history buffs that George Washington, in the waning months of the Revolutionary War, was "offered the crown" of the fledgling nation by a group of American military officers fed up with an ineffective Congress. Historians even have Washington's strongly worded rejection letter to prove it.

But a closer reading of original historical documents tells a different story. In this version, the widespread frustration of army officers gets mixed up with the pro-monarchy daydreams of one foolhardy colonel. Washington still comes out a hero, but he was never really close to being a king.

Advertisement

To set the scene, the British suffered a decisive defeat at Yorktown to American and French forces in 1781, resulting in the capture of 7,000 British troops and their leader, General Charles Cornwallis. The end of the war was finally near, but the beleaguered American Army, under the command of Washington, was still considered "on duty" until the Treaty of Paris was signed in 1783.

Back in those pre-Constitution days, the Articles of Confederation handed most power to the states, not the federal government. Congress had no power to tax, for example, which was a problem when it came to paying and equipping the army. Congress had to constantly request military funding from the states, which were often slow to pay up, if at all.

With peace nearly won, the army feared that Congress was going to stiff them on back pay. The officer corps were especially worried about their pensions, which they were promised would secure them financially for the rest of their lives. Could they trust Congress to keep its word and exact payment from the states?

Among the army officers sweating over his pension in 1782 was Colonel Lewis Nicola, a 65-year-old, Irish-born military veteran who lent significant expertise to Washington's forces during the war. Nicola and Washington corresponded frequently, usually about Nicola's duties as commander of the Invalid Corps, a garrison of injured soldiers who were still fit enough to serve.

But Nicola's letter to Washington on May 22, 1782 was something completely different. In this now infamous missive, Nicola opened with a reminder of what's at stake if the military wasn't properly compensated. Namely, the threat of open mutiny.

Then Nicola moved on to what he called his "scheme." He admitted to Washington that he wasn't a "violent admirer of a republican form of government," preferring instead a mixed form of government with elected representatives ruled by a benevolent monarch. And who better for such a leading role than Washington himself?

Washington's response, dated the very same day, was withering.

Washington's rejection of an American monarchy was absolute, but was a single letter from a presumptuous colonel the equivalent of being "offered the crown," as many believe?

Denver Brunsman, a history professor at George Washington University and scholar of the Revolutionary War and Washington, says that it would be an "exaggeration" to say that Washington was ever seriously offered the title of king.

"Nicola was not someone who was in the position to do that and I don't think he was part of any real, large movement," says Brunsman. "That doesn't mean there weren't people who had those sentiments and I think Nicola was representative of that. There were other individuals in the officer corps who were extremely frustrated with Congress and any hope for a possible solution."

"What's most important is Washington's reaction to even the notion [of being king]. He shuts down any possibility. I think that's impressive and shows why Washington was able to garner the trust of the American people."

Advertisement