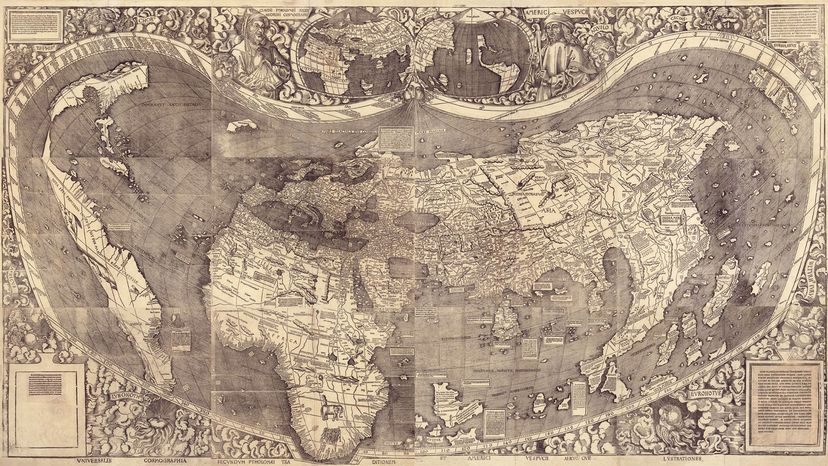

Everyone knows that Christopher Columbus "discovered" America in 1492, even though he never set foot in North America and died insisting that he had found a Western route to Asia. So why didn't the makers of the 1507 Waldseemüller map name the newly discovered lands "Columbia" instead of "America"?

Probably because Columbus didn't write a best-selling pamphlet about his travels full of sex, violence and naked cannibals like his fellow Italian explorer, Amerigo Vespucci, who sailed to the New World a decade after Columbus.

"Vespucci was a better self-promoter than Columbus," says Van Duzer, "and his accounts are more lurid, shall we say, than Columbus's, so they were reprinted more often."

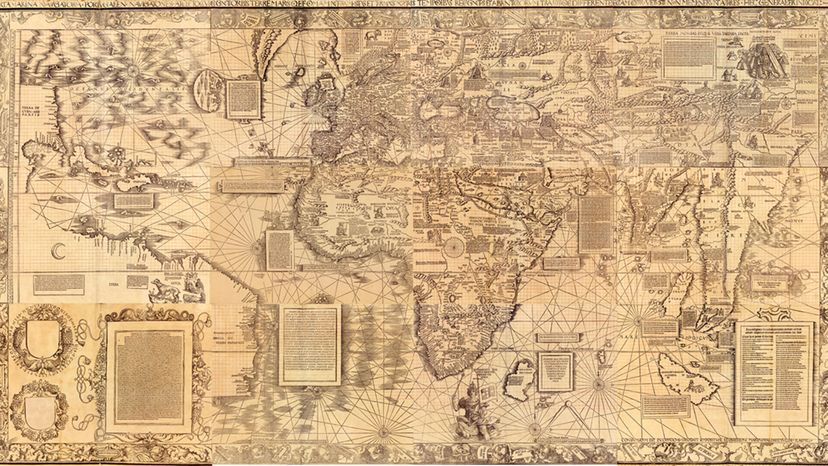

Vespucci published two wildly popular accounts of his voyages to the New World. The first, written in 1504, was called "Mondus Novis" and clearly asserted Vespucci's claim that the lands across the Atlantic were indeed a new continent, not an extension of Asia or just a big island.

"For this transcends the view held by our ancients... that there is no continent to the south beyond the equator, but only the sea which they named the Atlantic," wrote Vespucci. "But that this their opinion is false and utterly opposed to the truth, this my last voyage has made manifest; for in those southern parts I have found a continent more densely peopled and abounding in animals than our Europe or Asia or Africa." By following the South American coast to just 400 miles (643 kilometers) short of Tierra Del Fuego, Vespucci was convinced that he was traveling around a new continent.

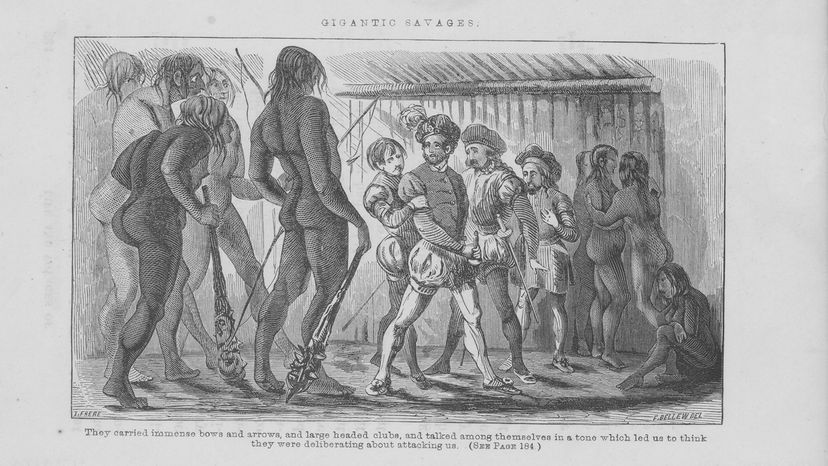

"Mondus Novis" also included plenty of colorful details about the "curious natives," whom Vespucci depicted as gentle and almost childlike in nature, but nevertheless barbarous and decidedly un-Christian in their customs, which included facial piercings, cannibalism and sexual promiscuity.

A second pamphlet known as the "Soderini Letter," which may not have been written entirely by Vespucci, made the rounds in 1505. The disputed text doubled down on Vespucci's descriptions of the naked locals and provided play-by-play accounts of a few violent clashes between Vespucci's men and the more aggressive tribes.

In one "laughable affair," Vespucci’s men welcomed some of the more adventurous Indians onto their ship where the Europeans decided to "fire off some of our great guns."

"[A]nd when the explosion took place, most of them through fear cast themselves (into the sea) to swim, not otherwise than frogs on the margins of a pond, when they see something that frightens them, will jump into the water, just so did those people," wrote Vespucci. "[A]nd those who remained in the ships were so terrified that we regretted our action."