In William Shakespeare's "Julius Caesar," the most fascinating character isn't the power-hungry Caesar, but his trusted friend and murderer, Brutus. Caesar's famous almost-last words in the play, uttered with disbelief as Brutus plunges the final dagger into the Roman dictator, are "'Et tu, Brute? (You too, Brutus?) Then fall, Caesar!"

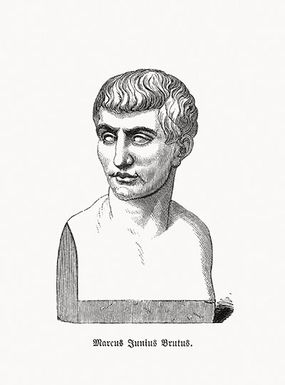

Marcus Junius Brutus (circa 85 B.C.E. to 42 B.C.E.) was a real person — a Roman statesman who was torn between his loyalty to Caesar, a longtime protector, and his loyalty to the Roman Republic. Ultimately, Brutus saw Caesar's tyranny as the greatest threat and, with his co-conspirator Gaius Cassius Longinus, instigated a Senate plot to kill him.

Advertisement

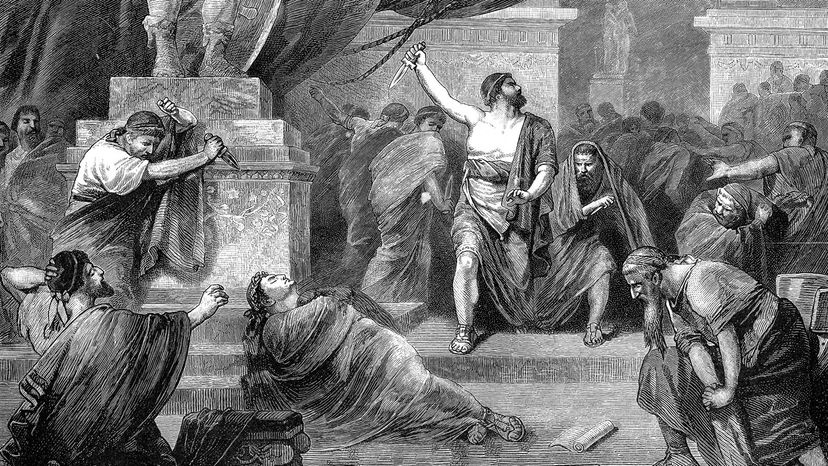

Brutus paid a terrible price for his "noble" betrayal of Caesar. Brutus quickly lost the battle for public opinion — the conspirators wanted to be known as "liberators" for freeing Rome, but they were labeled "assassins" — and then lost the military battle to Caesar's allies Mark Antony and Octavian.

From then, the name Brutus was synonymous with betrayal and treachery. Dante reserved the ninth and deepest level of hell for Brutus, Cassius and Judas Iscariot, the three ultimate traitors who are eternally consumed by the three mouths of Satan.

But who was the real Brutus, and what drove a respected politician and virtuous nobleman to stoop to such a low act? For answers, we reached out to Kathryn Tempest, author of "Brutus: The Noble Conspirator" and a reader of Roman history, Latin language and literature at the University of Roehampton London.

Advertisement