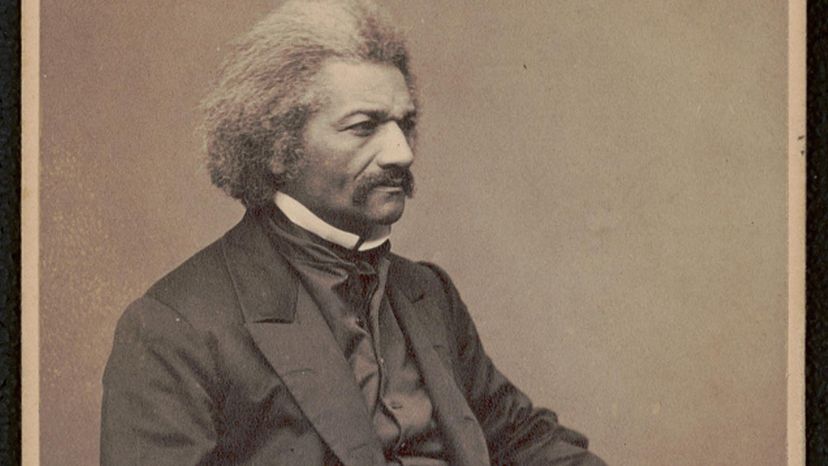

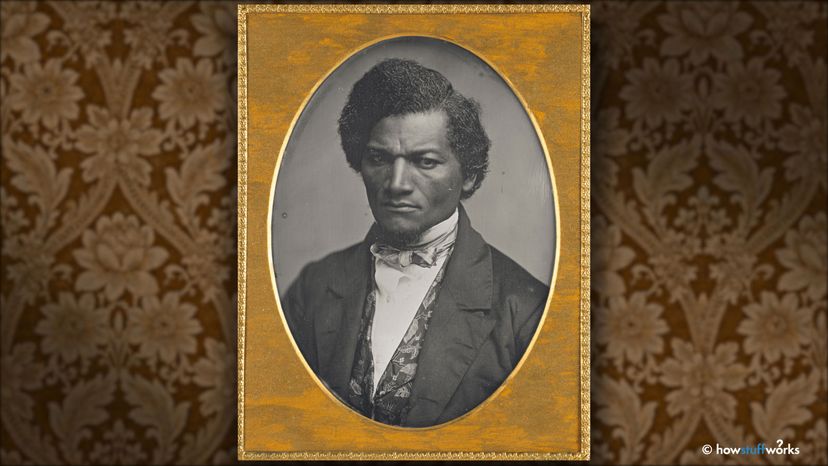

More than two centuries after the birth of Frederick Douglass, few men or women have come close to achieving his skills as both an orator and an agent of change. "Why we should remember him is because of what he represents to us even today. His ability to not only to speak truth to power but do so in such an eloquent way that he would challenge anyone who stands against him," says Pellom McDaniels, III, curator of African American Collections at Emory University's Rose Library. The power of Douglass' voice contributed greatly to the end of slavery, expansion of the right to vote and the general push toward equal rights for all that continues still.

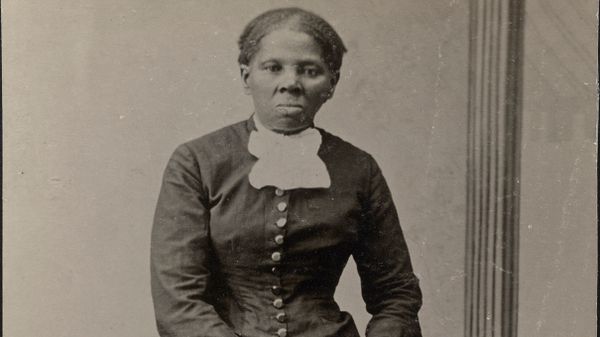

So, where did Douglass get that power? Born in 1818 as Frederick Bailey, he was a slave on the coast of Maryland. He recognized the value of literacy from an early age, and so he taught himself to read and write. He was hired out from age 8 to 15 as a body servant, and rebelled when his owner sent him to work in the fields. After a failed escape effort, he was sent back to Baltimore where he connected with Anna Murray, a free black woman. She helped him coordinate his escape and funded his train ticket, and as a result, he was able to make a break for New York City dressed as a sailor, where he was "free," but a fugitive, nonetheless.

Advertisement

Frederick married Anna, and the pair took the surname Douglass, in an effort to keep from being captured. They relocated to Bedford, Massachusetts, and eventually had five children.