Family dynasties in U.S. politics are not uncommon. Do the names Roosevelt, Kennedy and Bush ring any bells? But the original family dynasty was unquestionably the Adams family.

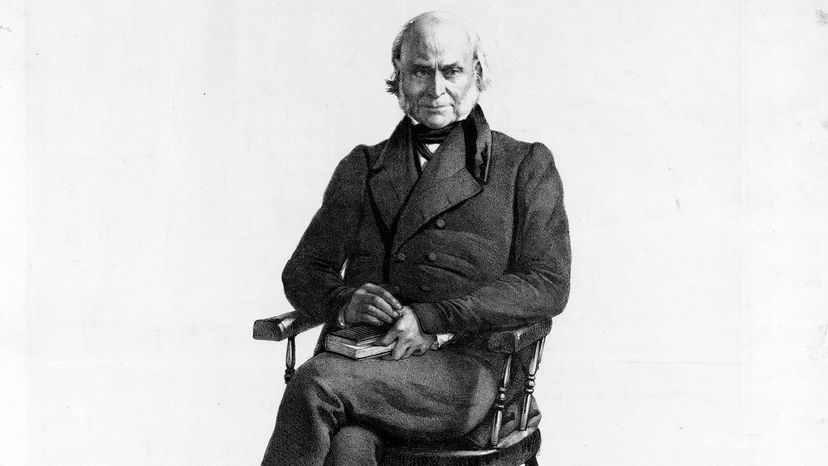

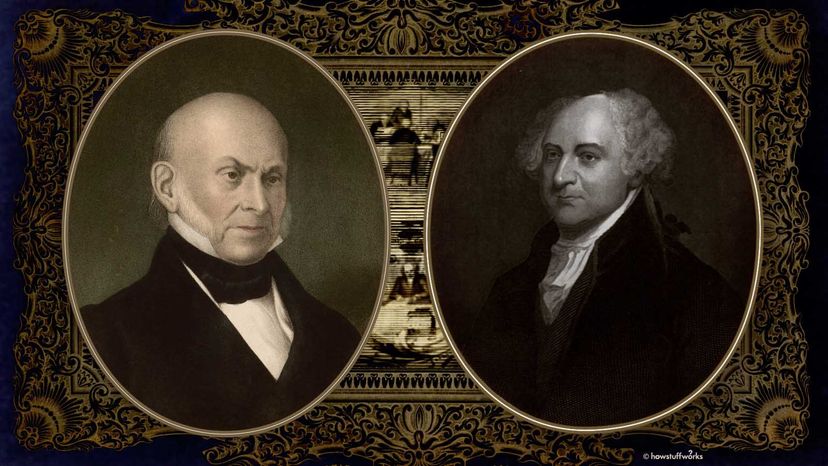

Founding Father John Adams served in the Continental Congress, as President George Washington's vice president, then as nation's second president (1797-1801). His eldest son John Quincy Adams was the country's sixth president (1825-1829).

Advertisement

But Adams and his son shared more than a career path.

"They both had a deep abiding duty to country and in the fundamental principles of American democracy," says Sara Martin, editor-in-chief of The Adams Family Papers, an extensive collection of Adams family writings owned by the Massachusetts Historical Society. "And they both spent the majority of their professional lives in service to the country."

Both men attended Harvard and studied law, though John Quincy also had the benefit of growing up as the son of "John Adams, Founding Father," and enjoyed some impressive experiences as a result. When he was just 10, he traveled to France with his father as John sought recognition and funds from the French government to support the American Revolution. When the support wasn't forthcoming, the father and son traveled to the Netherlands, where the Dutch came through with both recognition and financial assistance. When John Quincy was 14, he traveled to St. Petersburg to serve as a French-language interpreter and private secretary to Francis Dana, the U.S. Minister to Russia.

John served as America's first Minister to Great Britain. He negotiated the terms of the peace treaty to end the Revolutionary War and went to Paris for the signing in September 1783.

Advertisement