Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (who was famous for the quote "God is dead") was the son and grandson of Lutheran ministers. He was expected to follow their path, but the precocious young Nietzsche had his own ideas. And these were enormously influential in the 20th century.

Born in 1844 in a small town near Leipzig, Germany, Nietzsche excelled in school, played and composed music and was a fan of Ralph Waldo Emerson's essays. His papers on philology (the structure and development of languages) were so impressive that young Nietzsche was called to be the chair of philology at the University of Basel (Switzerland) before he even finished his doctoral dissertation at the University of Leipzig (Germany). He was only 24.

Advertisement

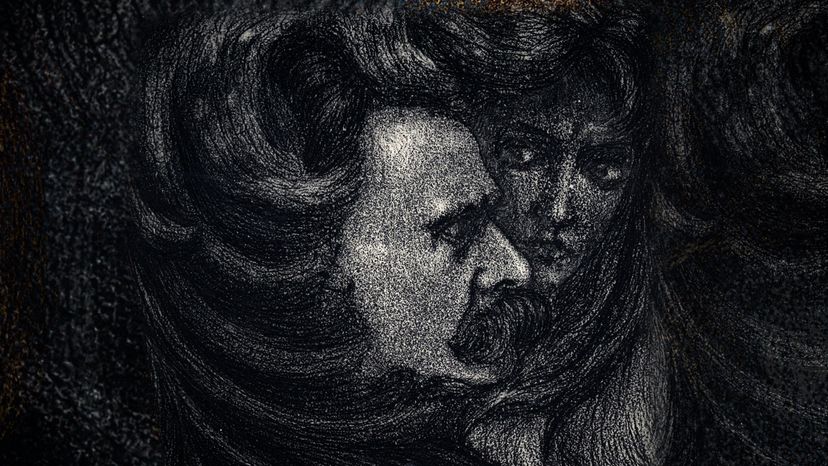

The Nietzsche we know, however, isn't the brilliant student of his early years, but rather the iconoclastic, mustachioed philosopher at the height of his intellectual and creative power. The author of books and essays with wickedly provocative titles like "The Anti-Christ" and "Beyond Good and Evil," Nietzsche said that the purpose of his work was to "overthrow idols" and "ideals." He had no patience for religious or philosophical views that looked beyond the earthly, human experience, and gleefully attacked conventional ways of thinking (including classical philosophy) with dagger-like strokes of his pen.

That said, Nietzsche isn't for everybody. His prose is playful and musical, but his meaning is often opaque. For example, Nietzsche loved to write aphorisms — short, pithy truisms that would fit nicely on a bumper sticker. But the aphorisms, while clever, often present more questions than answers. Here are a few from the opening chapter of "Twilight of the Idols":

All truth is simple." — Isn't that doubly a lie?

What? Is humanity just God's mistake? Or God just a mistake of humanity?

Reading Nietzsche, it's clear that you're in the presence of a rare genius, but unraveling the meaning of his grand pronouncements has kept scholars arguing for more than a century.

To help us make sense of Nietzsche's unconventional mind, we reached out to Dale Wilkerson, a professor of philosophy at the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley and author of the excellent entry on Friedrich Nietzsche in the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Here are five quotes from Nietzsche, starting with the most famous (and infamous) of them all.

Advertisement