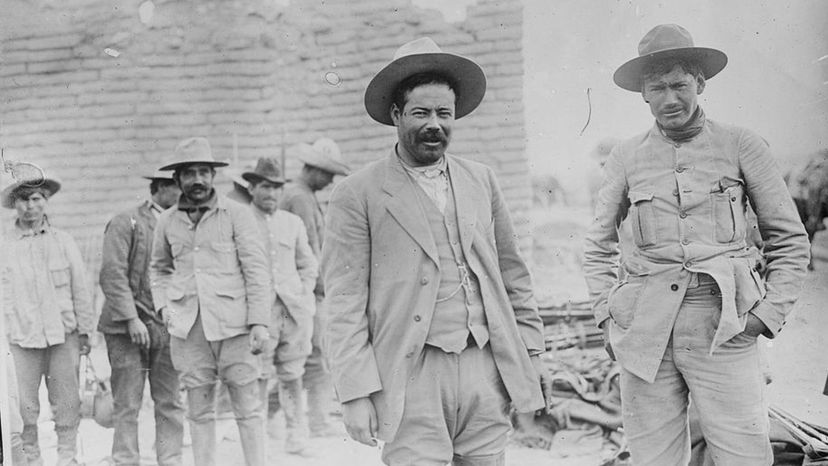

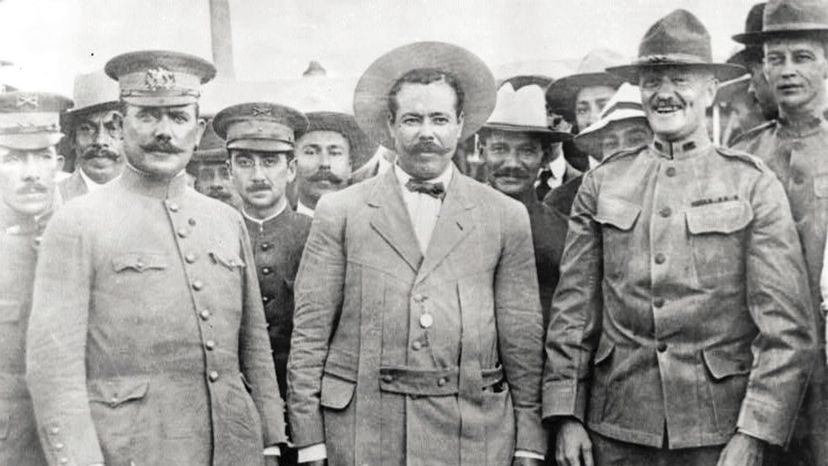

He's known around the world as a Mexican revolutionary and guerrilla leader, but there's a lot more to the mysterious Pancho Villa than many of us learned in school. Some have called him a modern-day hero and others consider him a bloodthirsty killer.

"His whole origin myth varies hugely depending on who is doing the talking," Paul Gillingham, associate professor of history and associate professor of Spanish and Portuguese at Northwestern University, says via email. "The Robin Hood version is that he is a poor sharecropper child who becomes an outlaw after defending his sister's honor against the local hacendado. The critical one is that he was a psychopathic career criminal. We don't have the information to know."

Advertisement

Despite the mystique that surrounds his legacy, what actually is known about the controversial figure who helped lead the Mexican Revolution and how did his efforts result in the end of Porfirio Díaz's reign and the creation of a new Mexican government? Here are nine facts you need to know about Pancho Villa.