Have you ever heard someone say "Nobody expects the Spanish Inquisition"? The line comes from a series of sketches by British comedy troupe Monty Python. In the sketches, one character gets annoyed at another character for asking him question after question. At the height of his frustration, he yells, "Well, I wasn't expecting the Spanish Inquisition!" Suddenly, three Catholic Cardinals burst into the room to comically "torture" the first two characters into admitting their sinful ways.

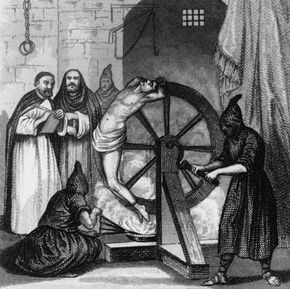

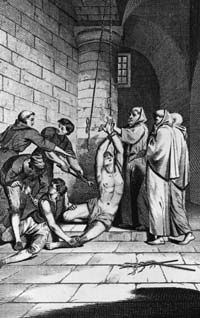

From the sketches, you can guess that the Spanish Inquisition must've involved torture and the Catholic Church. But why? Who was on the receiving end of that torture?

Advertisement

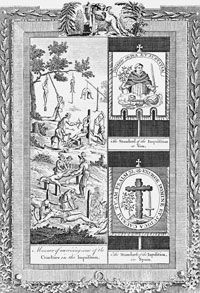

The Spanish Inquisition was just one of several inquisitions that occurred between the 12th and 19th centuries. In addition to the term being used for the historical events, the word "inquisition" refers to the tribunal court system used by both the Catholic Church and some Catholic monarchs to root out, suppress and punish heretics. These were baptized members of the church who held opinions contrary to the Catholic faith.

The inquisitorial system was based on ancient Roman law. It was different from other court systems because the court actually took part in the process of trying the accused. The term "inquisition" has a third meaning also -- the trials themselves.

Because of its association with torture and execution, inquisition remains a controversial and difficult subject. More than one hundred years after the last official act by the Office of the Holy Inquisition (now called the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith), the Vatican opened its secret archives to researchers to get at the truth of the inquisitions. In the next section, we'll find out how it all began.