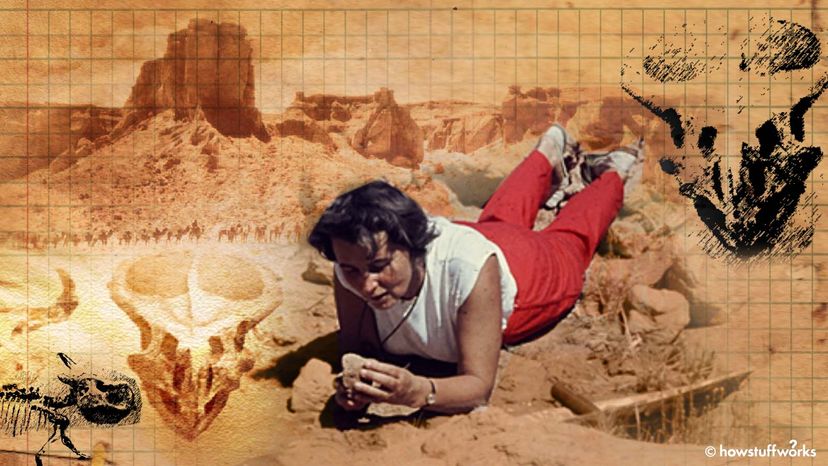

Scattered bones called out to her. On July 9, 1965, a visiting scientist — the late Zofia Kielan-Jaworowska — took a stroll through the Mongolian Gobi Desert. Little did she know she was about to discover one of the weirdest non-avian dinosaurs known to mankind.

Her 2013 book "In Pursuit of Early Mammals" describes the scene:

Advertisement

Strewn across a desert hill, the giant fossilized arms were unlike anything paleontologists had ever seen before. Each of these three-fingered limbs measured about 8.2 feet (2.5 meters) long. Impressed scientists named the animal Deinocheirus, which means "horrible hand."

From 1963 through 1971, Kielan-Jaworowska led several joint Polish-Mongolian Field Expeditions through the Gobi. The discovery of Deinocheirus in '65 was among their many highlights.

By the 1960s, Kielan-Jaworowska's name was well-known to scientists around the world. A preeminent paleontologist in her native Poland, she'd pursued her education at great personal risk during World War II.

Advertisement