Fisherman Jerry Murphy and his crew snagged something unexpected while trawling the Gulf of Mexico one afternoon in 1993. At first glance, the fishing net appeared weighted down with rock and debris. Upon closer inspection, some of those rocks were actually piles of silver coins, which had fused together while underwater. Realizing that he may have stumbled onto a deep sea treasure trove, Murphy dialed up his lawyer to attain rights to the booty, then contacted maritime history experts to determine the source of the coins [source: McConnaughey]. A year later, researchers concluded that Murphy's discovery -- which occurred, ironically, in a boat named Mistake -- was the ruins of a warship called El Cazador, or "The Hunter," that disappeared at sea in 1784.

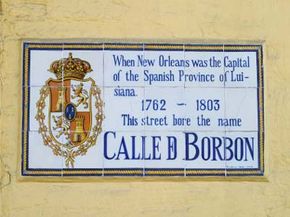

El Cazador set out from Veracruz, Mexico, loaded down with 19 tons (17 metric tons) of newly issued silver reales, or Spanish currency. King Carlos II of Spain ordered the money to be transported from the mint in Mexico to New Orleans, the capital of Spain's Louisiana colony. The king needed to pay his soldiers and government officials in charge of the city, but the paper money circulating in New Orleans had lost much of its value.

Advertisement

Not surprisingly, the city that lives by the motto "laissez les bon temps rouler" (let the good times roll) didn't always follow the letter of the law during colonial times. Situated in a relatively remote locale and settled by a fascinating hodgepodge of immigrants from France, Spain, Africa and the West Indies, New Orleans quickly developed its signature culture -- and a dash of Cajun corruption. A rash of counterfeiting and a shortage of hard currency devalued the cash in circulation, and left the Spanish government scrambling to compensate its employees.

On Jan. 11, 1784, El Cazador left Mexican shores, headed for the bayou. In June, the ship was declared missing, lost in murky depths for nearly 210 years. The more than 400,000 silver reales on board wasn't exactly pocket change for the Spanish government. That unlikely shipwreck gave King Carlos pause about whether the Louisiana Territory that Spain won from the French 20 years earlier was a worthwhile investment.

Advertisement