Your average citizen of ancient Greece did not, in his or her everyday life, spend much time worrying about the King of the Underworld. Greeks were polytheists. They had a bunch of gods to consider. Asking for blessings from the goddess of love (Aphrodite) or the god of war (Ares) was way more important than dealing with the god of the dead.

After all, everyone was going to come face-to-face with Hades at some point. No use in hurrying things.

Advertisement

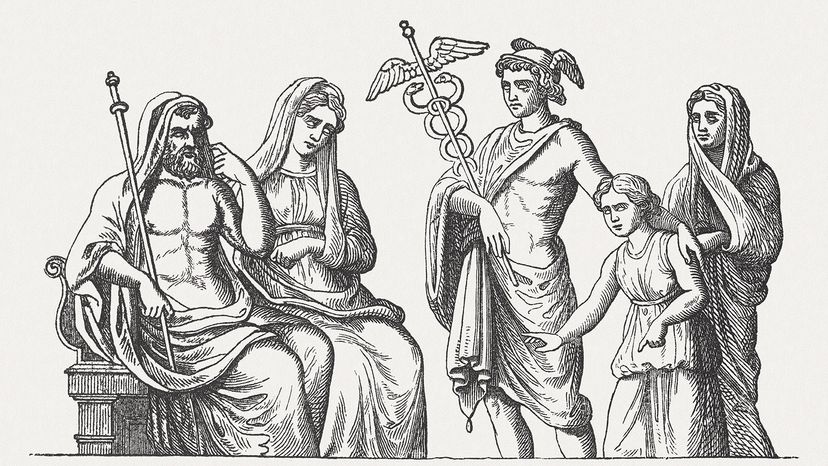

Still, Hades was a god and therefore commanded some respect from the Greeks. He and his brothers, Zeus and Poseidon, earned that status by knocking off the old-guard gods, the Titans, in a 10-year war known as the Titanomachy. Afterward, these new gods — the Olympians — split up the cosmos: Zeus, god of sky and the heavens (among other cool gigs), became king of the gods. Poseidon assumed control of the seas.

And Hades ended up with a mixed bag, ruling over both the dead and everything under the earth, including seeds, grains, gold and silver. It really wasn't as bad as it sounds. In fact, people ended up naming the underworld after him.

"He has this other name — Pluto — which means 'the rich one,'" explains Richard P. Martin, a professor of classics at Stanford University and the author of "Classic Mythology: The Basics" and several other books and articles on Greek, Latin and Irish literature. "The fact that he's connected also with [his pilfered wife] Persephone, who's connected with fertility and crops, gives you the impression that he's got a pretty good deal. He's the one who can kind of control what comes out of the earth. So it's not like he's got this kind of ... 'short straw' and he's in some dungeon.

"He was presented in this poem, "The Hymn to Demeter," as being a good catch, because he's rich and he's related to Zeus. So there's no sense in the ancient stuff, that I know, that he's somehow lost out and he's angry or something."

Advertisement