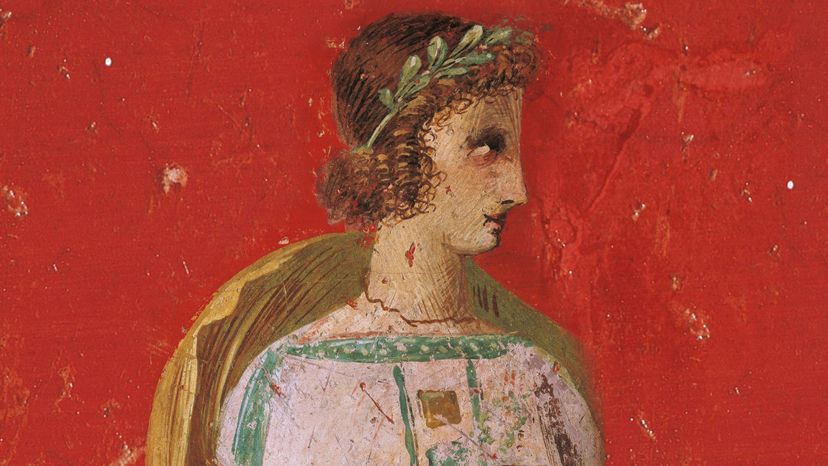

The story of how Hades kidnapped Persephone, goddess of spring, is one of the most oft-told stories from Greek mythology. What's often forgotten is how, despite the initial trauma of Persephone's abduction, she wound up enjoying her yearly stints as Queen of the Underworld during the cooler months of the year.

It can get difficult to keep track of all the Olympian gods the ancient Greeks worshipped. For that matter, most of them were relatives who married each other. Persephone's mother Demeter had plenty of cause for anger when her daughter became the wife of Hades. After all, he was her brother and Persephone's uncle! But then again, Demeter conceived Persephone with Zeus, another brother.

Advertisement

Confused yet? Take it all in and prepare to add more Greek mythology know-how to your growing knowledge bank because we asked Richard P. Martin, Antony and Isabelle Raubitschek professor in classics at Stanford University, to help us get to know the wife of Hades, Persephone.