The how of why Rockefeller died, according to Hoffman, is straightforward. He washed ashore, exhausted and weak from swimming for miles after the boat he and Wassing were in overturned.

On shore, he saw familiar faces — those of the Otsjanep warriors. Instead of the rescue Rockefeller hoped for, one of the men stabbed him in the ribs. The art-loving heir was killed in the precise actions of ritualistic headhunting, and the warriors consumed him.

According to Hoffman, the Otsjanep had never killed a white man before, and they knew Rockefeller to be a kind, respectful young man who paid well for their art. So why did they allegedly kill him?

There are two parts to this question. First, why did they kill Rockefeller? Second, why did they eat him?

Reacting to Colonialism

Ritualistic cannibalism, also called anthropophagy (cannibalism specific to humans) has been performed by various native cultures for thousands of years, particularly those in ecosystems with scarce food and resources.

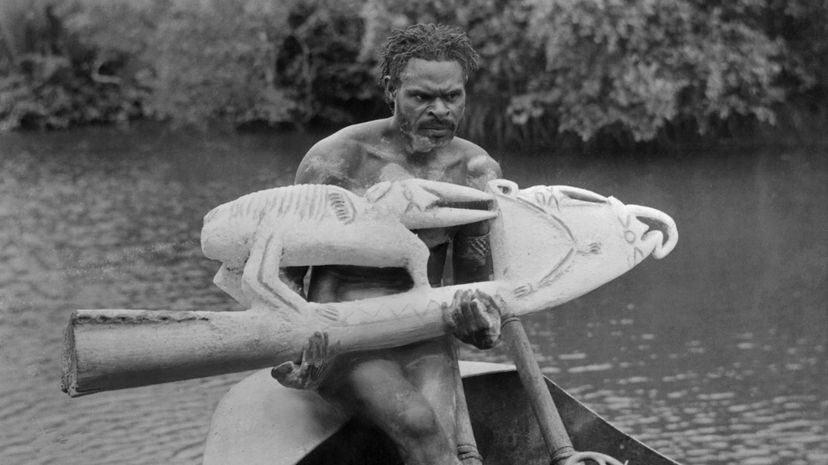

For the Asmat, cannibalism was not their sole purpose. Rather, it was only part of the sacred ritual of headhunting that brought meaning to their culture.

To understand why the Asmat killed Rockefeller in the first place is to know that his death was the result of hundreds of years of colonialism and a native people's struggle for the power to hold on to the deepest seeds of their culture.

"What happened with Michael," Hoffman says, "... was a moment of the Otsjanep, in particular, trying to retake and maintain their power in a world in which they were being stripped of it; the power of their own cultural view, power over their own destiny."