Salt gets a bad rap these days. Nutritionists are constantly reminding us to hide our salt shakers and eat low-sodium versions of our favorite foods. Salt is more than a spice; technically speaking, it's actually a mineral. Although too much salt is bad for us, the mineral itself is essential to a properly functioning body -- it helps us transmit electrical nerve impulses. Knowing how necessary salt is for the human body, it may not surprise you to learn that the mineral sparked one of the most significant national protests in modern history.

Long ago, people got their salt from the animals they hunted and devoured (raw meat is a good source of salt). But after they abandoned their hunter-gather lifestyles and became farmers, people replaced much of the meat in their diet with vegetables and grains; as a result, they needed supplementary sources of salt [source: Le Couteur]. Since ancient times, governments have recognized the benefits of taxing salt. Because everyone needs it, taxing salt ensures steady revenue. And because salt was also used to preserve food before the dawn of refrigeration, it was a popular commodity.

Advertisement

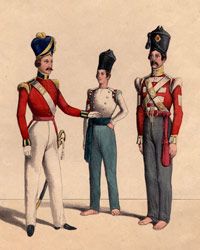

However, high salt taxes have often spurred controversy throughout history. The French tax on salt, known as the gabelle, even helped incite the French Revolution. In the 20th century, another salt tax inspired revolutionary action. This time it was in India, which was oppressed under British colonial rule. Similar to the way American colonists organized the Boston Tea Party 150 years earlier to protest British laws, Indians engaged in a peaceful and theatrical way to make their point.

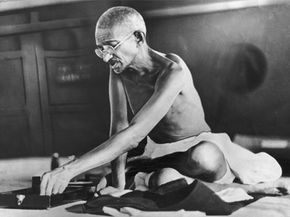

One prominent leader of the Indian independence movement, Mohandas (also known as Mahatma or "great-souled") Gandhi is noted for promoting a philosophy of civil disobedience. He believed that India could gain its independence from Britain through nonviolent campaigns. Salt came to the forefront of that campaign as an important issue and symbol of British oppression.

Advertisement