Key Takeaways

- Aztec death whistles were found in a Mexico City temple site, held by a sacrificed individual, and are believed to have had ritual and ceremonial significance.

- The death whistles are a unique type of "air spring" whistle, not fitting into Western classifications of wind instruments, and were likely used in rituals related to death and sacrifice.

- While claims of Aztecs using death whistles in battle remain unproven, a new tradition has emerged with artists and musicians incorporating the instrument into their own stories.

Buried beneath the streets and plazas of modern-day Mexico City are the ruins of ancient Aztec temples where human sacrifices were routinely performed to appease the gods. In the late 1990s, while excavating a circular temple dedicated to Ehecatl, the Aztec wind god, archeologists uncovered the remains of a 20-year-old boy, beheaded and squatting at the base of the temple's main stairway.

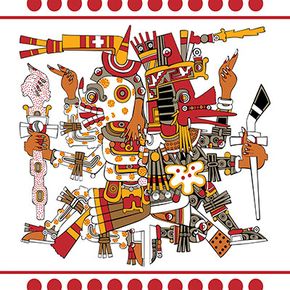

What made the Mexico City discovery so remarkable was that the skeleton of the human sacrifice was found clutching a pair of musical instruments in each hand. They were small, ceramic whistles decorated with a menacing skull's face. As the archeologists quickly realized, the skull image represented Mictlantecuhtli, the Aztec god of the underworld and of death itself.

Advertisement

And with that, the world became fascinated with a mysterious new instrument known as the "Aztec death whistle."

Today, if you Google "Aztec death whistle," you'll find articles claiming that the "haunting shrieks" of the death whistle were used to "terrify" the Aztecs' enemies in battle or to mimic the agonizing cries of sacrificial victims as their living hearts were torn from their chests. You can also watch this popular video clip of the late musician Xavier Yxayotl conjuring blood-chilling sounds from an oversized death whistle.

But the sober truth, experts say, is that we know very little about how the Aztecs really used these intriguing instruments or even how the instruments actually sounded when played by an ancient Aztec priest or musician. What we can safely infer from the find in Mexico City, is that death whistles undoubtedly had ritual and ceremonial significance, and that they may have been used to guide the spirits of the dead through the afterlife.

Advertisement