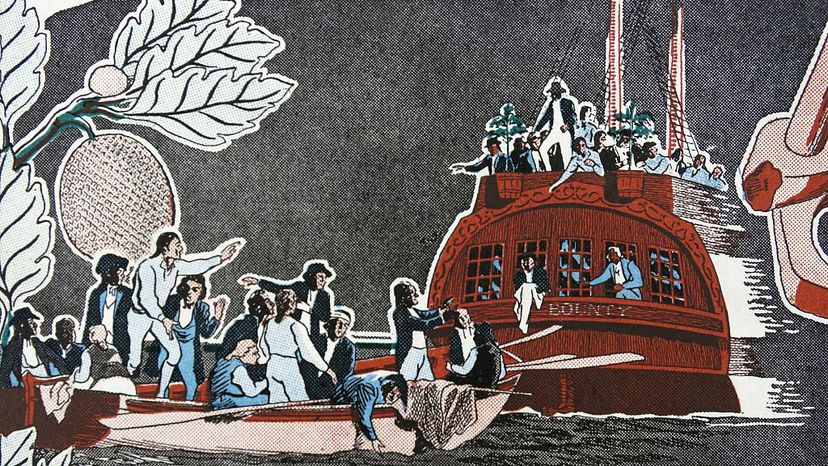

The "Mutiny on the Bounty" is one of the most famous tales in maritime history. The colorful story tells of a tyrannical British naval captain, William Bligh, who is overthrown by half his crew and sentenced to certain death in an overcrowded lifeboat with meager rations. But thanks to some brilliant seamanship and disciplined rationing, Bligh and his 18 loyal sailors survived 48 days crossing 3,618 nautical miles (about 4,163 miles or 6,700 kilometers) of storm-ravaged seas to make it to land and safely return to England.

The saga of the HMS Bounty has been the subject of three major motion pictures, all of which portray Bligh as the ill-tempered scoundrel, and Fletcher Christian, the dashing mutineer, as the hero. (A smoldering Marlon Brando played Christian in the 1962 version; Mel Gibson did the honors in 1984.) But nearly lost among the sensational details of the mutiny and Bligh's miraculous journey home is the reason why the Bounty had sailed halfway around the world in the first place: breadfruit.

Advertisement

Breadfruit is a tropical superfood, with each spiky, football-sized fruit packing loads of starchy calories as well as some protein, calcium and minerals. It can be eaten roasted, fried, boiled or even grated into flour. A single breadfruit tree can produce 250 fruits per season and remains productive for 50 years.

But why did breadfruit matter a lick to the Royal Navy in the late 1700s? Because the British Empire, which had recently lost 13 troublemaking colonies in North America, was rethinking its strategy for reaping maximum profit from its far-flung territorial possessions. Fueled by Enlightenment thinkers like Carl Linnaeus, the first true botanist, Britain was positioning itself as a global clearinghouse for food crops and other plants that could be uprooted from their native soils and put to work elsewhere in the empire.

The architect of this "botanical empire" was Joseph Banks, a wealthy British landowner and botanist who accompanied (and helped fund) Captain James Cook on his first exploratory voyage to the Pacific in 1769 aboard the HMS Endeavor. Banks discovered dozens of new plant species in his two-year journey with Cook, including the breadfruit, which grew on the Polynesian island of Tahiti.

At the same time, Britain was ramping up sugarcane production at its plantations in the Caribbean, primarily in Jamaica. The plantations were run on slave labor shipped in from Africa, and feeding the slaves, which numbered in the hundreds of thousands, was becoming increasingly difficult.

Back in England after his adventures with Cook, Banks conceived of an ambitious plan to transplant the prolific breadfruit trees all the way from Tahiti to Jamaica as a nutrient-rich food source for the slaves. And Banks knew just the man to do it, a proven seaman who served under Captain Cook on his third voyage to the Pacific, the 33-year-old Lieutenant William Bligh.

John McAleer is a history professor at the University of Southampton, and former curator of imperial and maritime history at the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich, England. He says that Banks's 18th-century vision of a networked empire that spanned the Pacific and Atlantic and Indian oceans marked the beginning of the globalized world.

In the 1790s, McAleer says, Britain was importing 20 million pounds (9 million kilograms) of tea from China, which wasn't a British colony like India, but still a valuable trading partner. Banks, in his botanical brilliance, saw a way to shuffle around Britain's global resources to "oil the imperial system."

"If you can get breadfruit from the Pacific to the Caribbean, you can make those slaves work harder and produce more sugar and more cotton, and then sell that and make more money to be brought to India and China to be exchanged for tea in Canton," says McAleer, co-author of "Captain Cook and the Pacific: Art, Exploration and Empire" with Nigel Rigby.

The mutiny almost spoiled Banks's plan. When Bligh's crew ditched him on the way back from Tahiti, they also dumped the breadfruit saplings into the drink. Incredibly, when Bligh miraculously made it back to England, he accepted a second assignment to go after the cursed breadfruit. This time it was successful, and Bligh finally arrived in Jamaica in 1793 with a floating nursery containing 678 surviving breadfruit trees.

Irony of all ironies, the enslaved people on the sugar plantations hated the nearly tasteless breadfruit and fed it to the pigs. Still, Bligh's breadfruit trees flourished in the Caribbean, and eventually, after some culinary experimenting, it became a staple of the Jamaican diet. Today the tree grows in some 90 countries.

Advertisement