Exhumations happen. Sometimes it's during a criminal trial; other times it's to identify historical figures; then there are times when it's used to simply determine paternity. Whatever the reason, there have been many cited cases throughout history when authorities have had to reexamine the physical evidence of the dearly departed.

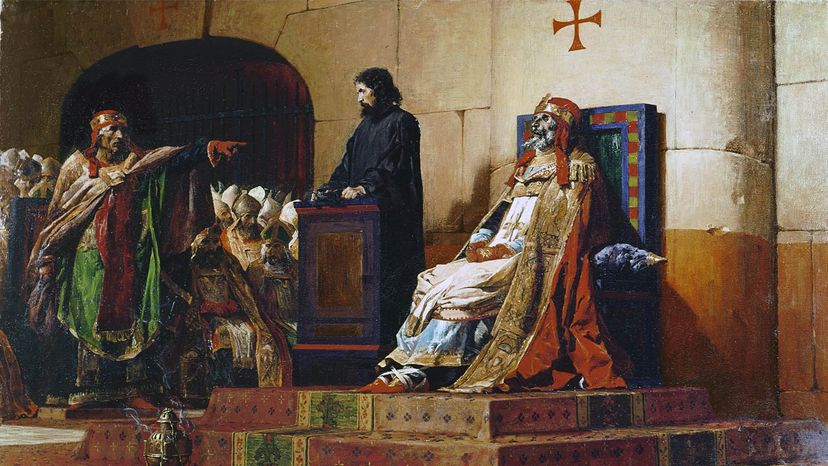

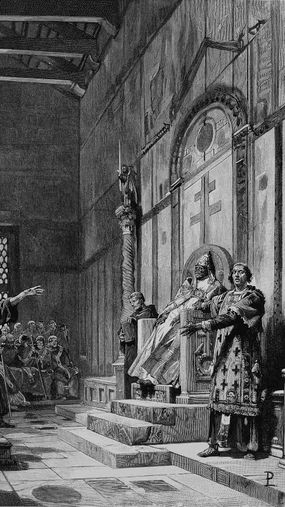

But having an actual cadaver stand trial for crimes already excused is when things start to get way more unusual. That's exactly what happened in 897 C.E. when the body of Pope Formosus was unearthed and taken to a courtroom presided over by the then-current pope whose only intention was to find Pope Formosus guilty.

Advertisement

The trial is known as the Cadaver Synod. The "cadaver" part is easy to understand considering Formosus' actual dead body sat accused. But if you're not familiar with the term synod, it is an ecclesiastical council or gathering where decisions about issues related to faith or disciplinary matters are determined.

While trying a dead body would be unimaginable in Vatican City today, the Cadaver Synod took place during a time when political machinations ruled the papacy, long before 11th-century reforms that regulated papal elections. It was a time when there was little distinction between private property and public trust, according to Rev. John W. O'Malley, S.J. Popes during the Middle Ages could dispense favor. It was a prize for a family to be aligned with the pope, and there were lots of rivalries. And like many stories, this one begins with the end of a great ruler.

Advertisement