Oliver Cromwell has the peculiar distinction of being the only political criminal to be executed two years after his death.

Yup, that's right.

Advertisement

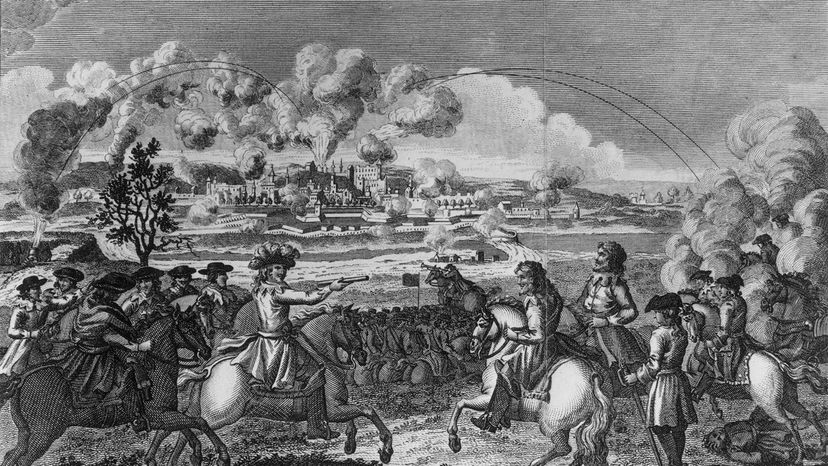

Cromwell, the controversial English historical figure who led the parliamentary revolt that ended with the execution of King Charles I, was exhumed from his grave in 1661 and put on trial by the late king's son, Charles II. Posthumously convicted of high treason, Cromwell's corpse was hanged and beheaded, and his head was impaled on a 20-foot (6-meter) spike outside of Westminster Hall.

In an age when drawing and quartering was also a popular punishment, it takes a special kind of traitor to warrant digging up his dead body and "killing" him again. But that's the level of loathing that Cromwell inspired in his 17th-century enemies, and that his name still provokes in places like Ireland, where Cromwell's troops committed wartime atrocities.

But Cromwell has his defenders, too. He dared to challenge the "divine right" of the British monarchy, oversaw the creation of England's (and arguably the world's) first written constitution, and was the first commoner to rule the short-lived British republic as its "Lord Protector." A devout Puritan, he also believed in religious freedom and tolerance, a cornerstone of modern Western democracy.

We reached out to Stuart Orme, curator of the Cromwell Museum in Cromwell's hometown of Huntingdon, near Cambridge, England, to learn why Cromwell remains one of the most important and divisive figures in British history.

Advertisement