French poet and historian Voltaire once wrote that the Holy Roman Empire was "neither holy, nor Roman, nor an empire." Given that the first true leader of the empire was Otto I of Germany, the Enlightenment thinker had a good point. Yet, the authenticity of the Holy Roman Empire's sacredness and imperialism doesn't shake out as easily. First, it's crucial to differentiate between the Roman Empire (think Caesar and Mark Antony) and the Holy Roman Empire (think Christendom and the pope).

The Roman Empire lasted from 27 B.C. to A.D. 476. In 395, the empire split into eastern and western divisions after the Emperor Constantine converted to Christianity. Constantine established Constantinople as the capitol of the Byzantine Empire in modern-day Asia Minor and the Balkans peninsula. German tribes invaded the western remnants and divided the land among the Goths, Lombards, Franks, Vandals and other clans.

Advertisement

Until 1453, the Byzantine Empire was more or less squared away, but the West spiraled into a frantic land grab. Jumping forward to the mid-700s, the Franks emerged as the most powerful Germanic clan in the West. Things got interesting when Pepin the Short, mayor of the Frankish palace, aspired to become the king of the Franks. Another royal bloodline, the Merovingian, still sat on the throne, but Pepin pulled enough weight as mayor to attract a powerful ally.

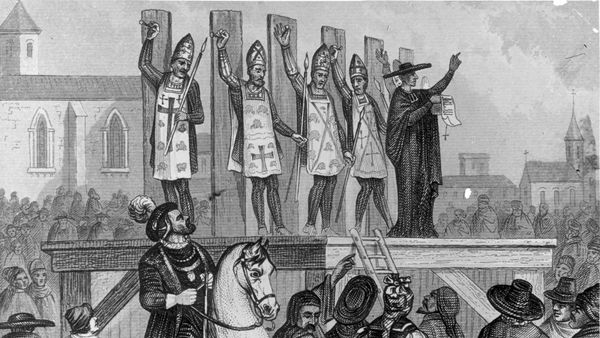

Pope Stephen II lived in northern Italy, nestled between the kingdoms of the Franks and Lombards. The pope sought Pepin's assistance because the Lombards attempted to overtake the papal territory. Seizing the opportunity for mutual gain, Pepin agreed to intervene with the Lombards in exchange for the Frankish crown; the pope was still the ultimate decider in Earthly matters.

Both parties made good on the bargain in 755. Pepin the Short conquered the Lombard kingdom, thus creating the papal states, and Pope Stephen II journeyed to the Frank kingdom to crown Pepin as king. That marked the first time a pope traveled such a long distance, symbolically legitimizing the change in royal lineage from the Merovingian to the Carolingian lineage [source: Barbero and Cameron].

By that time, King Pepin had two sons; the oldest, named Charles, would be known to history as Charlemagne.

Advertisement