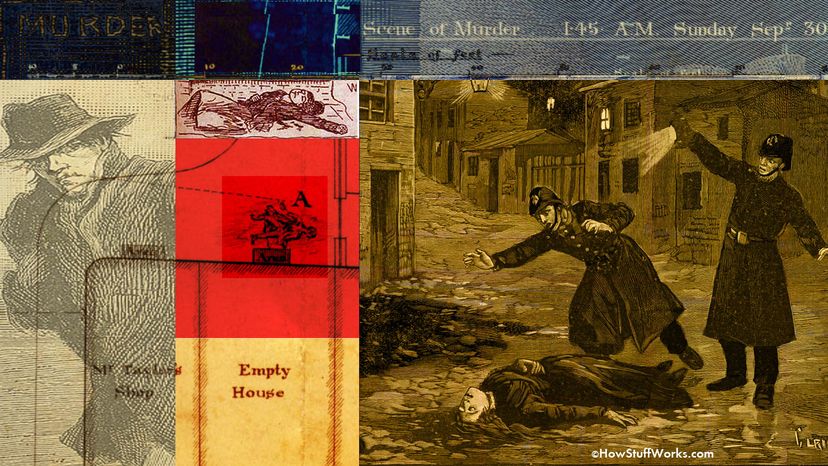

The East End of London was a dire place in 1888. Opium dens and brothels shared cramped quarters alongside family housing. Drunken residents spilled from the pubs into streets where children played. Violence was commonplace; cries for help of "Murder!" generally went unanswered [source: Haggard]. The living conditions in the East End reflected the poverty of its residents. There was precious little access to clean water, and diseases like tuberculosis and diphtheria spread easily. Some women engaged in casual prostitution to supplement their families' incomes. It was a bleak, depressing and often menacing place to live [source: Peyro].

Which makes it all the more significant that in the fall of that year, a series of murders were committed that were so brutal — so contrary to any degree of humanity — that they stood out starkly against this grim backdrop and captured the attention of the entire world.

Advertisement

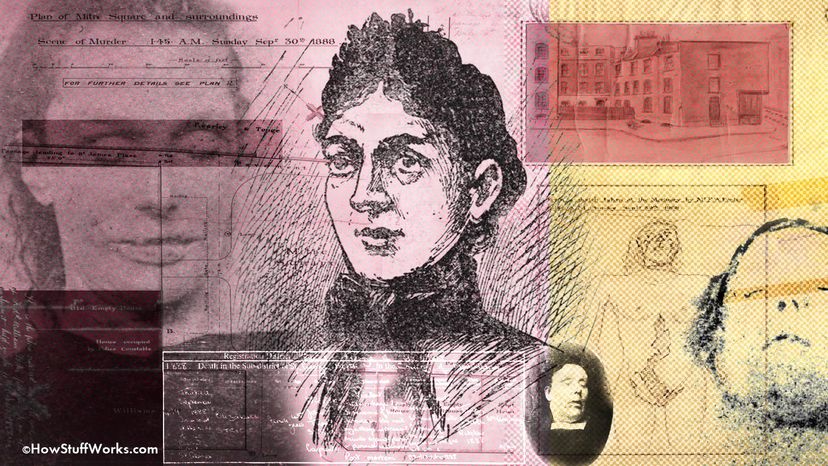

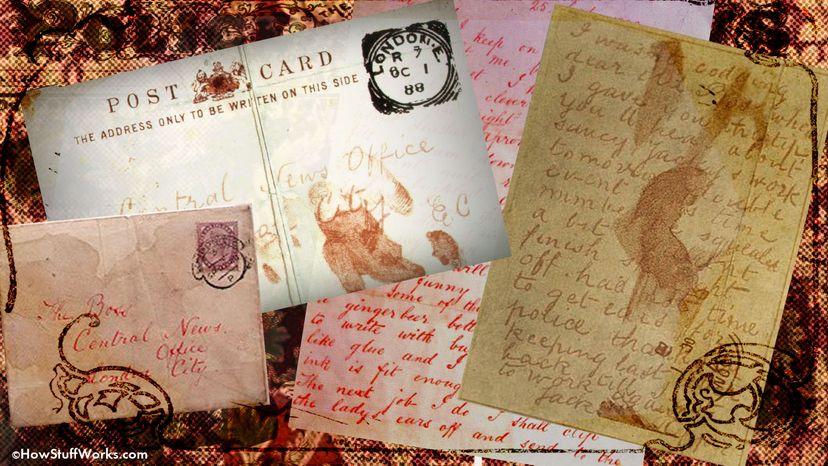

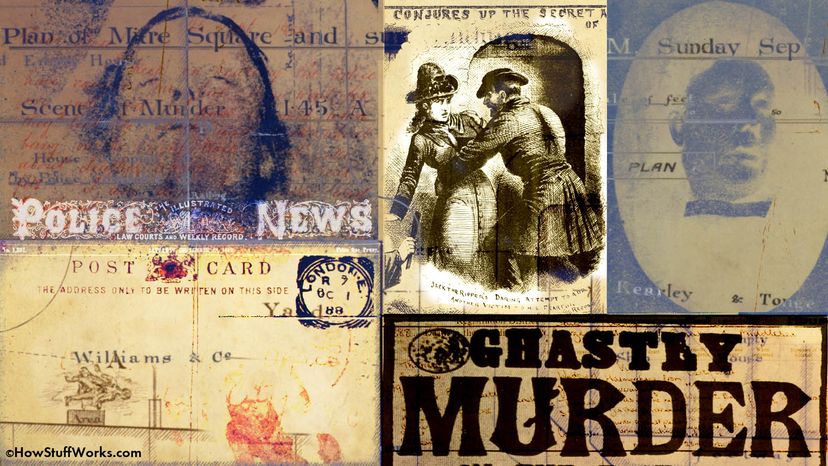

In the East End's Whitechapel district, a string of prostitutes was butchered. The crime scenes were a gory tableau; the brutalized bodies were perversions of the human form. The killer was a collector who took organs as trophies. The signature of a letter that arrived during the murders gave this monster a name: Jack the Ripper [source: Peyro].

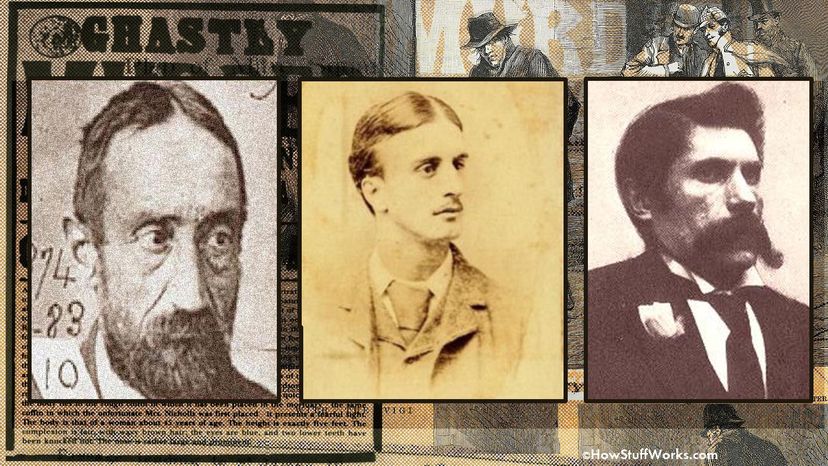

The city was whipped into a froth of suspicion and fear. Wide dragnets snagged scores of suspects, but the police were unable to catch the killer. A vigilance committee of local business owners hired unemployed men to roam the streets at night, armed with sticks and whistles, in hopes of catching the killer [source: British Library]. And then, suddenly, the murders stopped. Despite three more years of investigation, the police never uncovered the true identity of Jack the Ripper. The unsolved case was officially closed in 1892, though interest in the killings has never dwindled [source: Barbee]. A thriving subculture of amateur criminologists — Ripperologists — has been cultivated by the enduring mystery of Jack the Ripper.

The further one delves into the study of the Ripper murders, the easier it becomes to imagine them through Jack's eyes. What did he feel in the hours before he murdered, while he hunted for victims? Perhaps he toyed with the women, buying them drinks in pubs like the Brittania and then leaving their company, only to meet up again one last time later that evening. He must have been giddy with power, believing that he held in his hands the fate of each woman he passed.

We will never know the veracity of these ideas. But there are some safe assumptions about the Ripper and his personality that criminology — both contemporary and modern — has provided.

As the slayings continued, Jack the Ripper's modus operandi (M.O.) — the methods he used in each murder — became clear. He struck only in the early hours of morning and only on weekends. These facts are revealing. For one, they suggest the Ripper was single, since he was able to keep late hours without arousing suspicion. Secondly, they point to the idea that he was likely regularly employed during the week, which would explain his inactivity Monday through Thursday [sources: Casebook, Slifer].

The Jack the Ripper case gave the modern world its first exposure to the harrowing concept of the serial killer. But the details of the case are so far-flung, incomplete and exaggerated in some instances that for many years, it seemed that the identity of the murderer would never be uncovered. Recently, however, DNA analysis has pointed toward a suspect. But before we get into that, here are the facts about the women whom Jack the Ripper killed in such horrifying fashion.

Warning: This article contains graphic descriptions of historically documented murders.

Advertisement