Did you know that two other men accompanied Paul Revere on his famous midnight ride? If you didn't, then you're not alone. The story of the midnight ride was stamped on the American psyche by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's popular 1861 poem "The Midnight Ride of Paul Revere." And anyone who's read the poem envisions a lone hero dashing through the night, single-handedly warning his countrymen of a British attack.

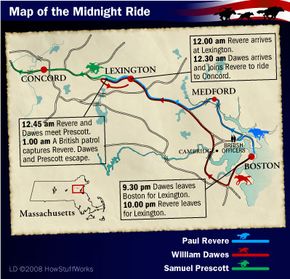

But that's not the whole story. Two other men rode with Revere that night: William Dawes and Samuel Prescott. They were left out of the poem and subsequently most history books.

Advertisement

Some joke that Longfellow used Revere's name in his poem -- instead of Revere's comrades' names -- simply because it was easier to rhyme with other key words. In fact, a woman named Helen F. Moore wrote a parody poem in 1896 titled "The Midnight Ride of William Dawes." The poem compares Dawes' and Revere's accomplishments, but complains, "What was the use, when my name was Dawes!"

More likely it was Paul Revere's established political fame in the Massachusetts Bay Colony that landed him his starring role in the Longfellow poem. A silversmith by trade, he spent most of his free time supporting the patriots' cause. He had participated in the Boston Tea Party to protest taxation without representation -- one of the main events leading up to the Revolutionary War. And he was known as a reliable courier for news and messages that needed to be distributed to patriot leadership, so much so that the British even had someone tracking his movements.

But truth be told, it was really Samuel Prescott who completed the midnight ride. Read on to find out how the three riders carried out their mission on the night of April 18, 1775 to start the American Revolution.

Advertisement