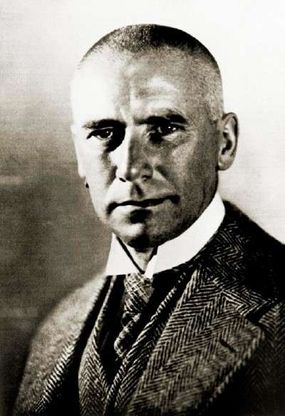

In early 1943, President Franklin Roosevelt and Winston Churchill discussed the future direction of the war and agreed to maintain a relentless bombing campaign against the European Axis states to ease the pressure on the Red Army. This Combined Bomber Offensive was the Allies' substitute for a second front, which was deemed too risky in 1943. In May 1943, the German navy lost 41 submarines while Allied merchant vessel losses dropped sharply. Over the next two months, a further 54 submarines were sunk, prompting the German naval commander-in-chief, Admiral Karl Dönitz, to withdraw from the North Atlantic.

The Allies' critical victory over the submarine menace made possible the broad extension of American military and economic power into the European Theater.

Advertisement

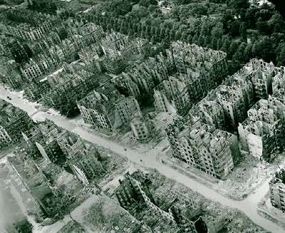

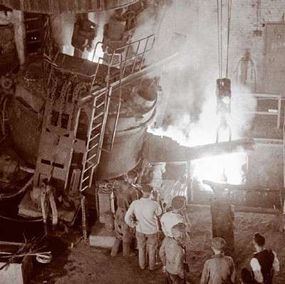

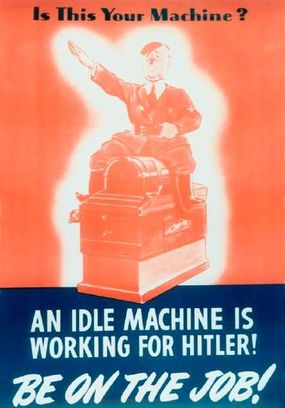

In 1943, that power was principally represented in the air. The Combined Bomber Offensive was officially launched as Operation Pointblank in June 1943, although British Bomber Command and the U.S. Eighth Air Force had begun around-the-clock bombing -- the British by night, the Americans by day -- from the winter of 1942-43. The offensive was aimed at the enemy's military-economic complex -- the source of German airpower and the morale of the urban workforce.

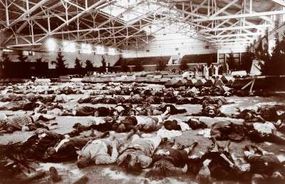

Efforts to attack identifiable industrial or military targets could not be achieved with prevailing technology without a high cost to civilians. From July 24 to 28, a succession of attacks on the northern German port city of Hamburg resulted in the first "firestorm," which killed an estimated 40,000 people. Over the course of the war, more than 420,000 German civilians would die from the bombing attacks; a further 60,000 civilians would be killed in attacks on Italian cities.

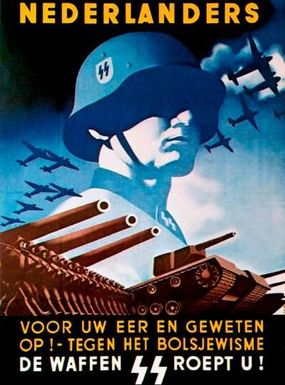

The bomb attacks immediately affected German strategy. The Germans established a large air defense sector. To do so, they had to withdraw valuable resources of manpower, artillery, shells, and aircraft from the military front line. There, German armies were forced to fight with shrinking air cover. Though military production continued to rise in Nazi Germany during 1943, the increase was much lower than it would have been otherwise. Bombing placed a ceiling on the German war effort and brought the war to bear directly on German and Italian society.

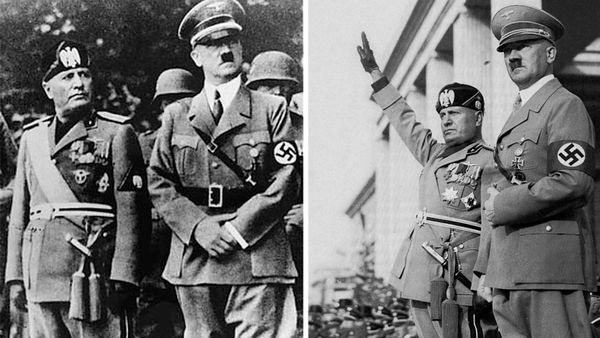

The Allies capitalized on these growing advantages. In North Africa, the Axis forces that were bottled up in Tunisia were slowly starved of supplies by Allied naval and air power in the Mediterranean. By May 13, when the battle was over, 275,000 Italian and German troops had surrendered. As had been decided at Casablanca, the Western Allies launched an attack on Sicily on July 9-10, 1943. During the capture of the island, Mussolini's regime was overthrown by the Fascist Grand Council and the monarchy. On September 3, an armistice was agreed upon, and on September 8, Italy surrendered.

That same week, American and British Commonwealth forces landed in southern Italy against limited German resistance. However, German forces were reinforced as the battle took shape. Though Naples was liberated on October 1, Allied progress slowed in the difficult mountain terrain. By the end of 1943, the German army -- which had formally occupied Italy as an enemy state -- consolidated a strong line of defense, the Gustav Line, south of Rome.

The Allies' pressure at sea, in the air, and on the southern front made the Axis task in the Soviet Union more difficult. Following the collapse of the German assault on the Caucasus and Stalingrad, the Red Army became overly ambitious. After the Soviets pressed the German army back, a swift counteroffensive around Kharkov in early 1943 was a reminder that the huge German army remained a formidable foe. Hitler listened to the advice of his generals, who argued that in summer weather, with good preparation, they could smash a large part of the Soviet Union army in a single pitched battle. They chose a large salient that bulged into the German front line around the city of Kursk as their battleground.

Operation Citadel lacked the geographical scope of previous operations, but it became one of the largest set-piece battles of the whole war. It followed a classic German pattern: Two heavily armored pincers would close around the neck of the salient, trapping the Soviet Union armies in the salient and creating conditions for a possible drive into the areas behind Moscow. Manstein, who commanded the southern pincer, wanted to attack in April or May, before the Red Army had time to consolidate its position. But Hitler, in agreement with General Model (who commanded the northern pincer), ordered a delay until German forces were fully armed with a new generation of heavy tanks and guns -- the Panthers and Tigers.

The Soviet Union, for the first time, guessed the German plan correctly. Stalin had to be persuaded by Georgi Zhukov and the General Staff that a posture of embedded defense was better strategy than seeking open battle against a powerful mobile enemy. Stalin accepted it only because the defensive stage was to be followed by a massive blow struck by Soviet Union reserves against the weakened and retreating German armies.

In May and June, a vast army of Soviet Union civilians turned the Kursk salient into a veritable fortress. Six separate defense lines were designed to absorb the expected shock of the German armored assault. The Red Army numbered 1.3 million, the Germans 900,000. Each side had approximately 2,000 aircraft and more than 2,500 tanks. On July 5, German forces began the attack. They made slow progress over the first week against determined Soviet Union resistance. Zhukov's plan worked, and for the first time in the two years of fighting on the Eastern Front, a large-scale German campaign was held and then reversed without the crisis and retreat that had preceded other victories.

On July 13, Hitler canceled Operation Citadel after news of Allied landings in Italy. But at just the moment that German forces pulled back, the Soviet Union punch into the rear of the northern pincer was delivered. The German army had not expected a counterstroke of such size and ferocity. Over three months, they were pushed back across the whole area of southern and central Russia. On November 6, Russian forces reentered the Ukrainian capital of Kiev. The Battle of Kursk, more than any other single engagement of the war, unhinged the German war machine and opened the way to victory in the East.

In the midst of the euphoria of victory, Stalin traveled to the Iranian capital of Tehran for the first summit conference with his Western partners. The central issue was a second front in the West. Though Stalin now privately argued that his forces could finish the job without Western help, the Red Army continued to suffer a terrible level of loss that could not be sustained indefinitely in a single-front ground war. After two days of argument, in which Churchill tried to insist on a strengthened Mediterranean strategy at the expense of invasion, Roosevelt was able to promise Stalin an operation in the spring of 1944 that would bring American and British forces in strength into northwestern Europe. One witness recalled a sober, pale-faced Stalin replying, "I am satisfied with this decision."

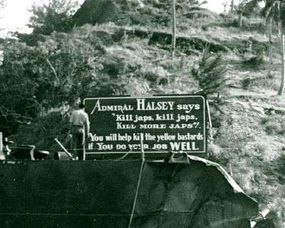

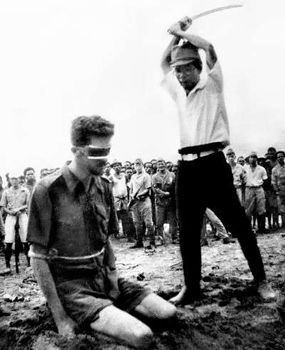

In the atmosphere at Tehran, it was easy to forget that another war was being fought in Asia and the Pacific that was quite distinct from the conflict in Southern and Eastern Europe. There, it was still possible for the Japanese to attempt further expansion. In October 1943, the Japanese army undertook military operations in central China designed to erode the spread of Chinese communism. The Communist forces were led by Mao Zedong, who had devoted much of the Communist efforts to maintaining independence from the Chinese Nationalist army of Chiang Kai-shek.

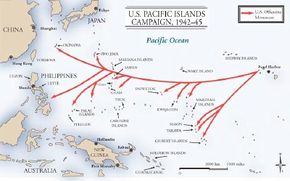

In the Pacific Theater, the Japanese defeat on Guadalcanal was followed by a slow American advance through the Solomon Islands and a combined American and Australian campaign in New Guinea. Japanese air and naval strength could not match the United States' huge production programs. And though the Allies' move through the islands of the southern and central Pacific, code-named Operation Cartwheel, was slow and costly, it proved unstoppable. By the end of 1943, the central Solomons had been occupied and progress had been made on New Guinea. Japan's major base at Rabaul was bypassed.

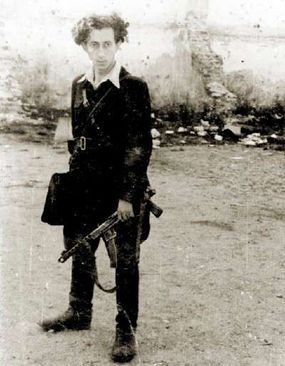

Throughout the region, Japanese garrisons were left to themselves in strategically unimportant places, increasingly hungry and sick but supplied by submarines. In the rest of the Japanese empire of occupation, imperial rule was consolidated. Anticolonial and anti-European movements were encouraged. The Japanese encouraged the formation of the Indian National Army under the leadership of nationalist Subhash Chandra Bose, who recruited 18,000 Indian prisoners of war to the cause in Southeast Asia. They were tolerated only as long as they fought for the Japanese. For millions of others in the so-called Great East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, one form of domination had been exchanged for another. In China, more than 10 million people died during the course of the war with Japan in a conflict largely unnoticed by the rest of the world.

Continue to the next section to learn more about crucial World War II events in the second half of 1943. A detailed timeline of events from late June to early July 1943 is included.

To follow more major events of World War II, see:

- World War II Timeline

- Italy Falls to the Allies: February 1943-June 1943

- The D-Day Invasion: January 1944-July 1944

Advertisement