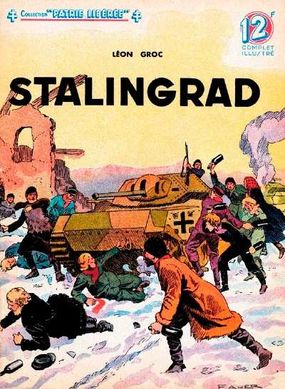

The Nazi German armies that moved relentlessly toward Stalingrad in summer 1942 during World War II were confronted with a bleak terrain. "A barren, naked, lifeless steppe," wrote Johann Wieder, who survived the conflict to write his memoirs, "without a bush, without a tree, for miles without a village."

For a time, the advance appeared to be a repeat of the summer of 1941. The Sixth Army of General Friedrich Paulus pushed the Soviet forces in front of it. By August 19, they had reached the outskirts of Stalingrad. On August 23, the first formations reached the banks of the Volga River. Paulus promised Hitler that the city would fall within a few days.

Advertisement

In reality the attempt to seize Stalingrad turned into one of the epic battles of World War II. During the five months in which the battle for the city raged, the advance of the Axis powers was halted and crushed. By the time Friedrich Paulus surrendered in early February 1943, the tide had begun to turn not just on the Eastern Front but also in the Middle East and the Pacific.

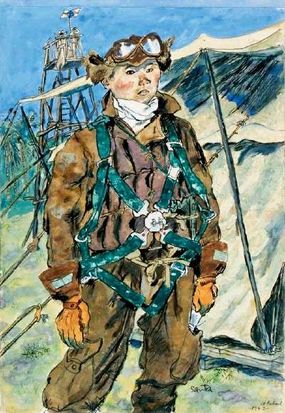

Following the Japanese defeat at Midway Island in June 1942, the Allies found it possible to begin the long and brutal campaign to dislodge Japan's forces from the string of islands they had occupied around the ocean perimeter of the Empire. This was a difficult and costly campaign for both sides. Men and equipment had to be transported over long oceanic supply lines, thousands of miles from the home countries, and in terrain where tropical heat and disease took a high toll on the combatants, as did some of the bitterest fighting of the war.

The first battles were fought in southern New Guinea and the Solomon Islands, deemed by Japanese planners to be areas in the new perimeter that needed to be consolidated. In New Guinea, Japanese forces attempted, by an overland campaign, to seize Port Moresby, which they had tried to secure three months earlier by sea. The battle against Australian and American forces continued for six months until finally, on January 22, 1943, the last Japanese troops were cleared from the central portion of the huge island.

American forces landed on Guadalcanal and Florida Island in the southern Solomons on August 7, 1942. There, against fierce resistance, they captured the port of Tulagi and the airfield on Guadalcanal. The U.S. needed six months to secure these modest gains against fierce resistance that was repeatedly reinforced. However, the American capacity to supply large numbers of planes and trained pilots slowly tilted the conflict toward the Americans.

All Japanese efforts to destroy the tenuous American foothold were beaten off. At the end of December 1942, the Japanese high command decided to abandon the contest, having lost more than 20,000 men, 600 aircraft, and 15 warships in the attempt. Though Allied gains on New Guinea and in the Solomons had been modest, it was now clear to both sides that Japan was fully stretched by commitments in the Pacific and China, and lacked the capacity for further advance.

In the Middle East, Nazi German general Erwin Rommel advanced into Egypt and toward Palestine. However, this apparently disastrous position for the Allies was stabilized and then reversed. As in the Pacific, both sides were fighting far from the home base and at the end of supply routes, which were regularly threatened by submarine and air action.

By autumn 1942, British Empire forces had succeeded in building up large reserves while Axis supplies were regularly interrupted by submarine action in the Mediterranean. North Africa mattered differently to each side as well. For Adolf Hitler, North Africa was a sideshow. For the Allies, it was a vital part of their global strategy; the Middle East and Mediterranean should not be abandoned to the Axis.

Nevertheless, Erwin Rommel had achieved a great deal. On August 31, 1942, he began a final offensive designed to bring him into Egypt and Palestine so that the Jews there could be killed before the area was turned over to Italy. Like the Japanese, he discovered that his overstretched resources had reached their limit.

The British Eighth Army, which was dug in on a line near the small Egyptian city of El Alamein, absorbed Rommel's assault. On October 23, with overwhelming materiel advantage, a new British commander -- General Bernard Montgomery -- launched a counteroffensive. His 1,030 tanks proved too large an obstacle for the 500 or so Axis tanks that opposed him, and by November 4 Axis forces were in full retreat.

Bernard Montgomery did not cut off the Axis retreat, but by early February, Axis forces had been pushed back into Tunisia. Many of the Italian units were destroyed, and thousands of soldiers were taken prisoner. Once again, as in the Solomons, airpower had played a critical role in the Allies' success.

The change in fortunes owed something to the willingness of the Allies to collaborate. The three Axis powers made little attempt to coordinate their strategies, share economic resources, or divulge military or technical secrets. The Western Allies recognized earlier how important it was to share resources. They also understood how vital it was to mobilize their extensive manufacturing and scientific capacity as fully as possible to compensate for their lack of a large and experienced army.

The United States sent large amounts of food, raw materials, and equipment to Britain. So, too, did Canada, whose contribution is often overlooked. The Soviet Union was the beneficiary of a rich flow of resources from both North America and the British Empire, including a half-million vehicles and a million miles of telephone cable.

The Soviets received few weapons, but the provision of food, manufactured products, and materials allowed the Soviet economy -- which had lost around 60 percent of its capacity in 1941 -- to concentrate on the mass production of armaments.

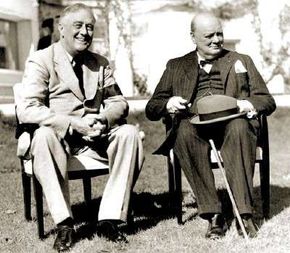

The help was sourly acknowledged, because Joseph Stalin wanted his allies to launch a second front in 1942 to take the pressure off the Red Army. In August 1942, Winston Churchill flew to Moscow to discuss Allied strategy face-to-face. It was a difficult confrontation.

Joseph Stalin implied that the British were simply afraid of the Nazi Germans. Winston Churchill's furious rebuttal finally won over Stalin. He was told of Western plans for an expanded bombing campaign against Nazi German targets and of a still-secret operation, code-named "Torch," of Allied landings in northwest Africa, planned for November.

The invasion of North Africa began on November 8, 1942. Like operations in the Pacific, the American task force sailed the whole width of an ocean to reach the Moroccan coast on November 7. British forces landed at Oran and Algiers.

After brief fighting with French colonial forces, the whole area was secured three days later. The Allied armies rushed toward Tunis to cut off the retreating Erwin Rommel. The Nazi Germans deployed enough forces into the pocket from Italy to create a stable front line, and the battle for Tunisia began in the last week of November.

In retaliation, Adolf Hitler ordered Nazi German forces to occupy the whole of Vichy France, which was absorbed into the German New Order. Jewish refugees who had managed to hide in the unoccupied zone were now pursued with a new vigor. As Axis forces found themselves pressed on all fronts, the mass murder of Jews reached its crescendo in the death camps at Auschwitz, Sobibór, Belzec, Chelmno, and Treblinka.

The gains in other theaters paled in comparison to the struggle that had engulfed the southern front in the Soviet Union. Nazi German expectations that the city of Stalingrad would quickly fall were frustrated by many factors: Nazi German forces had to be supplied along a single rail track into the battlefield.

The destruction of the very large city by Nazi German bombers created the ideal conditions for a determined infantry defense. And most of the buildings were modern steel and concrete structures with bunkers and cellars beneath them, which meant that not even regular shelling and bombing could easily flatten what was left of the twisted structures.

Into this wrecked landscape, the remnants of Soviet divisions retreated. They hid in the crumbled buildings and underground hiding places, attacking in small groups, often at night. Soviet sharpshooters pinned down Nazi German forces, which for most of the battle greatly outnumbered their opponents.

The commander in Stalingrad was a young Soviet general, Vasily Chuikov. The son of a peasant, Chuikov was robust and unflinching in the face of battle. His 62nd Army was scattered in pockets of what remained of the center of Stalingrad. It was supplied across the Volga River from the east bank, from which came waves of artillery and rocket fire, a stream of Soviet air attacks, and large numbers of soldiers.

On several occasions, his weakened forces were close to collapse, but Paulus lacked the means to launch a knockout blow. The last major Nazi German offensive, designed to sweep Chuikov's remaining troops into the river, began during the second week of November. On the 8th, Adolf Hitler told the party faithful in Munich that in days he would be "master of Stalingrad."

The swift retreat on the southern front had been a shock to Joseph Stalin, who was determined to hold the city which now bore his name. In mid-September, his deputy commander-in-chief, General Georgi Zhukov, worked with the army staff on a possible way out of the crisis.

Rather than throw more troops into the Stalingrad pocket, he suggested building up massive reserves on the Nazi German flanks that could be used to cut the German line of advance and encircle Friedrich Paulus's troops. As long as Chuikov could hold the city, the plan -- Operation Uranus -- would work.

Further north, Georgi Zhukov planned Operation Mars, another large assault on the Nazi German line. This operation would prevent any German reinforcement of the south and might unhinge the whole Nazi German front line in the Soviet Union.

This was the first time Soviet commanders had been able to plan, with Joseph Stalin's approval, a large-scale counteroffensive. Preparations were made under the strictest secrecy.

On November 19, Soviet armies fell on the unprepared Axis forces. Because they lacked the forces to guard the flanks of their advance, the Nazi Germans had pushed their Romanian, Italian, and Hungarian allies to increase their commitment of troops to the Eastern Front. Since the Nazi Germans had failed to provide these troops with proper equipment, the Romanian front was torn apart and Paulus was encircled.

Nazi German field marshal Erich von Manstein launched a counterattack to break the ring, but failed. Axis forces retreated back across the steppe. In the Caucasus, Soviet armies drove the southern Nazi German front back as well, though they failed to close off all avenues of escape. The success of Uranus masked the mixed fortunes of Operation Mars, in which the Red Army suffered very heavy casualties for virtually no strategic gain.

After another two months of bitter fighting, Friedrich Paulus and his shrunken army of diseased, hungry, and frostbitten soldiers finally surrendered on February 2, 1943. The remnants of the remaining Axis forces in the north of the city surrendered two days later. Some 91,000 Axis soldiers were taken prisoner.

This defeat, far more than the victories elsewhere, signified to the world that the Axis was not invincible.

Let's take a closer look at these World War II events, beginning with a timeline of early August 1942 on the next page.

Learn more about the significant events and players of World War II in these informative articles:

- World War II Timeline

- Italy Falls to the Allies: February 1943-December 1943

- The Axis Conquers the Philippines: January 1940-July 1942

Advertisement