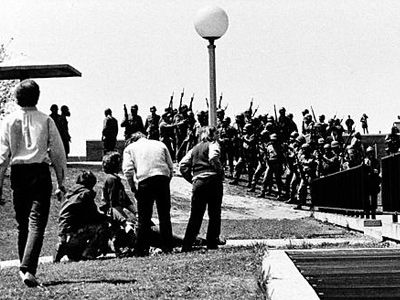

In the early 1970s, two college students felt compelled to take action during a time when most Americans felt particularly helpless and even hopeless. The war in Vietnam had been raging since the 1950s, but it wasn't until 1964 that a pilot named Everett Alvarez, Jr. became the first United States prisoner of war (POW), which led President Lyndon B. Johnson to increase the draft to 35,000 troops each month. Within a few years, hundreds of American soldiers were dying each week and many more were taken as POWs or considered missing in action (MIA).

Carol Bates Brown and Kay Hunter, described as two "sorority-type" college students in Los Angeles, wanted to find a way to offer families some solace. The two came up with a novel idea: making bracelets to commemorate the American prisoners of war suffering in captivity in Southeast Asia. By the late '60s, Brown served as the National Chairman of the POW/MIA Bracelet Campaign for VIVA (Voices In Vital America), the Los Angeles based student organization that produced and distributed the bracelets.

Advertisement

In 1969, television personality Bob Dornan (who would later be elected to Congress) introduced Brown, Hunter and several other members of VIVA to three wives of missing U.S. pilots. The women asked the student group to help draw public attention to those missing in Vietnam. While petitions and protests were certainly options, Brown and Hunter "were looking for ways college students could become involved in positive programs to support U.S. soldiers without becoming embroiled in the controversy of the war itself."

And so, the bracelets became a major part of the publicity plan. Dornan had begun wearing a bracelet he got in Vietnam from native hill tribesmen, which he said reminded him of the suffering that resulted from the war. "We wanted to get similar bracelets to wear to remember U.S. POWs, so rather naively, we tried to figure out a way to go to Vietnam," Brown wrote in an article on the origin of the bracelets. "Since no one wanted to fund two sorority-girl types on a tour to Vietnam during the height of the war, and our parents were livid at the idea, we gave up..."

It was then that Hunter began investigating ways to make bracelets but ended up leaving VIVA. Brown then collaborated with student Steve Frank and adult adviser Gloria Coppin to pursue the POW/MIA awareness program.

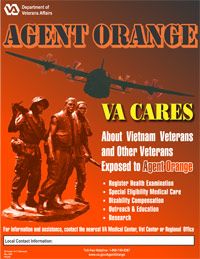

While significantly fewer Americans were taken prisoner during Vietnam versus previous wars (726 compared to more than 4,000 during World War I, 130,000 during World War II, and 7,000-plus in Korea), families were far more aware of their suffering. In an effort to extinguish public support for the war, North Vietnamese soldiers publicly displayed POWs in propaganda campaigns. Americans wanted to wear their support on their sleeves; Brown and her team found a way to allow citizens to wear it on their wrists.

In late summer 1970, Coppin's husband donated enough brass and copper to make 1,200 bracelets at 75 cents a pop, which the VIVA team sold to students for $2.50 and to adults for $3. Each bracelet was engraved with the name, rank, service, loss date and country of loss of a missing soldier.

"On Veterans Day, November 11, 1970, we officially kicked off the bracelet program with a news conference at the Universal Sheraton Hotel," Brown wrote. "Public response quickly grew and we eventually got to the point we were receiving over 12,000 requests a day." The income allowed VIVA to pay for promotional items like bumper stickers and buttons and gave bracelets to relatives of missing soldiers so that they could be sold on consignment. By the time VIVA closed its doors in 1976, the organization had distributed nearly 5 million bracelets and had "raised enough money to produce untold millions of bumper stickers, buttons, brochures, matchbooks, newspaper ads, etc. to draw attention to the missing men."

Brown says the public was tired of hearing about Vietnam by then and "showed no interest in the POW/MIA issue" but memorial bracelets are still available for sale, even today and news stories continue to recount the legends associated with the original items.

Advertisement