World War I wrought unprecedented levels of death and destruction, claiming upward of 30 million military casualties and millions of civilian lives and livelihoods. The four-year slaughter finally came to an end on Nov. 11, 1918, but the final terms of Germany's capitulation weren't hammered out until the Paris Peace Conference of 1919.

U.S. President Woodrow Wilson chose to attend the peace negotiations in person, becoming the first American president to travel abroad on official business. Wilson arrived with an idealistic vision of a rebuilt Europe safeguarded by a new League of Nations, as outlined in his famous "14 Points" speech. The French and British, however, who had lost millions of soldiers during years of brutal trench warfare, came demanding justice and revenge.

Advertisement

After months of contentious negotiations, to which Germany and the other defeated Central Powers weren't even invited, Wilson and his allied counterparts emerged with the Treaty of Versailles (so-called because it was signed at the Palace of Versailles in France). The sprawling document redrew Europe's borders, carving new countries out of the former Austro-Hungarian empire (including Yugoslavia, Czechoslovakia and Poland) in a nod to Wilson's policy of "self-determination." But the harshest terms of the treaty were reserved for Germany.

The German military was effectively disarmed and reduced to a defensive skeleton force. Germany lost 10 percent of its territory, including the long-contested Alsace-Lorraine region and all of its overseas colonies. Allied forces would occupy German territory west of the Rhine for 15 years.

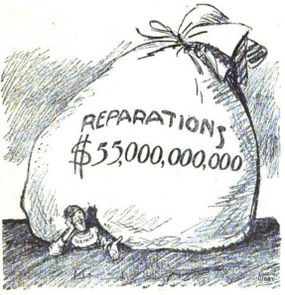

And then there was the matter of reparations. In order to demand that Germany pay back Allied countries for the damage it inflicted to life and property, the Treaty of Versailles needed to officially assign blame. That explains the inclusion of "Article 231," also known as the "War Guilt Clause":

Germany was eventually billed for $32 billion (over $500 billion in today's dollars) in damages, an astronomical sum for a nation gutted by war and still without a functioning government. Defeat and debt were bad enough, but the shame and guilt imposed by the Treaty of Versailles were seen by many Germans as intolerable.

"From a political standpoint, [the War Guilt Clause] does more harm than good," says Michael Neiberg, chair of war studies at the U.S. Army War College and author of "The Treaty of Versailles: A Concise History." "It stirs up everybody inside Germany. It gives them something to unify against at a time when Germany is badly divided on what should replace the Kaiser's regime. Now you've given them a single thing to rally around."

Advertisement