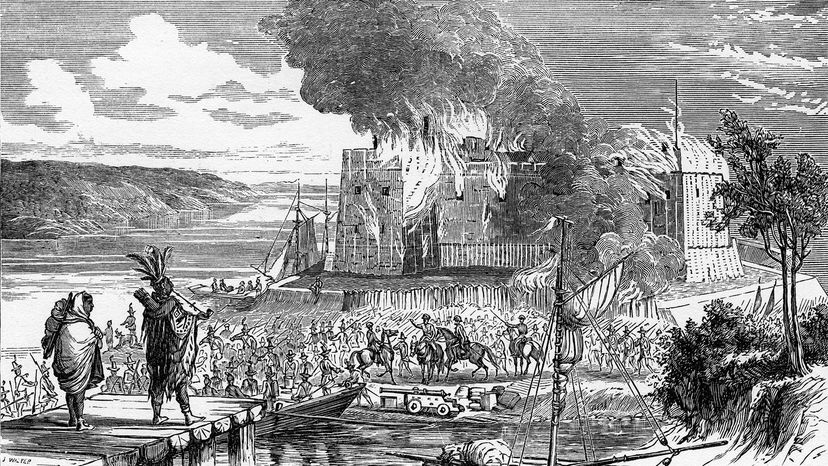

The name is confusing, right? It sounds like the French and Indians were fighting each other. But the French and Indian War was the North American theater of engagement between two imperial powers — Great Britain and France — battling it out for world dominance. In that regard, some students of history, including former British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, call the French and Indian War (also called the Seven Years' War) the first "real" world war because, not only did it include the two most powerful armies at the time, but they also fought on multiple fronts — in Europe, in colonies in the West Indies and even as far away as India.

"The world was turned upside down by the Seven Years' War," says John Giblin, director of education and engagement for the U.S. Army Heritage and Education Center at Carlisle Barracks, Pennsylvania (also home to the U.S. Army War College). Giblin is the former director at the Fort Pitt Museum and Bushy Run Battlefield in Pennsylvania, and was one of the creators of the 2006 War for Empire project, commemorating the 250th anniversary of the French and Indian War.

Advertisement

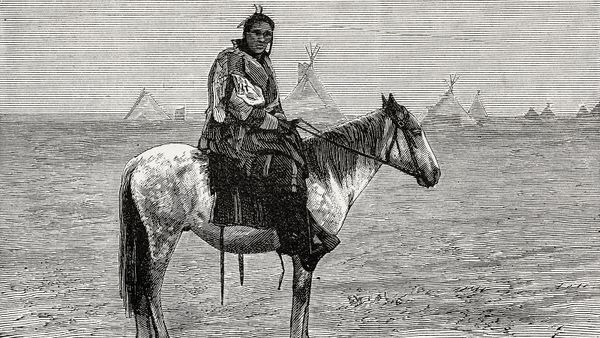

"You had superpowers, you had colonial governments vying for states or colonial rights, you had indigenous peoples attempting to hold on to what they believed they rightfully owned and you had adventurers in the mix, trying to get their piece of the pie," Giblin adds. "It was an extremely tumultuous time. There was no one winner; everyone got something, but lost something. But it set the stage for how the world was going to change."