The Black Codes were short-lived. The U.S. Congress, frustrated with attempts by Southern lawmakers to sidestep Reconstruction, passed the Civil Rights Act of 1866, which affirmed that Black Americans must be afforded the same civil rights enjoyed by white people.

In the wake of the Civil Rights Act, the federal government imposed what's known as "Radical Reconstruction" on the former Confederate states. During this time, Black men were given the right to vote and run for political office, and thousands of public schools opened across the South to serve Black children.

The Black Codes may have been nullified, but their legacy would echo down through racist post-Reconstruction laws and the indignities of Jim Crow laws that were enacted in the South in the 1890s and lasted all the way to the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 60s.

"The Black Codes laid the framework for how this whole system is going to work for the next 100 years," says Bailey. Jim Crow laws made it illegal for Blacks and whites to share any public facilities, meaning that both groups had separate schools, libraries, hospitals, restaurants, etc. with Blacks receiving inferior facilities to whites. Laws were enacted requiring literacy tests and/or poll taxes to be paid before voting, all designed to disenfranchise poor African Americans.

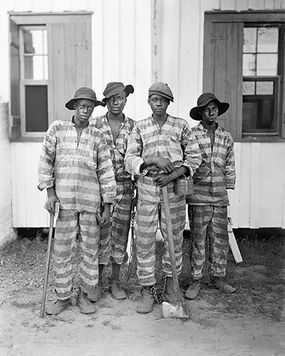

In "Slavery by Another Name," Blackmon wrote about a Black man named Green Cottenham who was arrested in 1908 in Alabama for "vagrancy," the same trumped-up charge invented 40 years earlier by the Black Codes. Cottenham was auctioned off to the northern corporation U.S. Steel, who chained him in a suffocating Birmingham, Alabama, coal mine and tasked him with mining 8 tons (7.25 metric tons) of coal a day until his fine was repaid. If he collapsed from malnourishment or fatigue, he would be whipped. And if he died, he'd be buried in a shallow, unmarked grave with the rest. More than 1,000 Black men were toiling for U.S. Steel along with Cottenham in the same mine. In less than year, 60 were dead from disease, accidents or homicide.

Blackmon called this shameful chapter of American history "neo-slavery" and it was all set in motion by the Black Codes.

HowStuffWorks earns a small affiliate commission when you purchase through links on our site.