Witchcraft theorists and interrogators of the 15th century obtained their testimony through intimidation and torture — and as such the confessions of their victims matched and even exceeded their expectations for supernatural evil and debauchery.

So how did such testimony arise in the late 20th century without the aid of thumb screws and breaking wheels? Why through the interrogation of impressionable, young children of course.

By the late 1970s, child abuse was already a trending topic in American media coverage. Reports of kidnapping, child murder and child pornography outraged and sickened the public — and rightfully so. In 1978, the death of children at the Jonestown religious commune in Guyana blurred the lines between real-life fringe religious movements and fictional satanic cults.

Then, in 1984, allegations of sexual abuse at California's McMartin preschool and the lengthy trial to follow firmly established the notion of satanic ritual abuse (SRA) in contemporary America. The trial ended six years later in acquittal and dismissal, but the fantastic allegations created a media feeding frenzy. Prosecutors charged that a ring of teachers had sexually abused hundreds of children in rituals that involved robes, masks, pentagrams and altars.

Numerous cases sprang up across the United States, all following the pattern set by the McMartin case. Often, the incident would begin with a single, plausible accusation of realistic abuse. Then, the subsequent investigation would lead to therapist-derived accounts of wider abuse, each fueled by leading questions and the impressionable child's eagerness to provide suitably shocking details [source: Jenkins].

By the mid-1990s, hundreds of day care workers and parents had been accused of and, in many cases, convicted of SRA [source: Frankfurter]. Make no mistake: Satanic ritual abuse had become an actual diagnostic and criminological category.

But satanic panic entailed a perceived threat not only to the children of the present, but also to the children of the past. After all, such a well-connected cult of secretive Satanists had surely been targeting children for quite some time. Perhaps even your childhood contained an incident of satanic ritual abuse. All you needed to do was reclaim the buried memory of the encounter.

This is where the reclaimed memories movement of the 1980s enters our understanding of the panic. Proponents theorized that traumatic memories — especially childhood sex abuse — can become buried in the subconscious. While essentially forgotten, these bits of emotional shrapnel still could negatively impact your life. The only answer was to allow a therapist to dig them out with recovered-memory therapy (RMT).

The issue is a sticky one to say the least. For starters, most childhood sex abuse victims at least partially remember what happened to them. In the rare event that such an incident or incidents are forgotten, the victim can certainly remember it later — but they can just as likely construct a convincing pseudomemory, or false memory [source: APA].

Remember, memories are not set in stone. If anything, the medium is soft clay: highly susceptible to manipulation by ourselves and others each time we draw them from storage. In fact, Harvard psychologist Daniel Schacter recognizes no fewer than seven different factors that can inhibit accurate recall, including the power of suggestion. Fantasy, social conditions and cultural influences can all color the recollection. Once created, a pseudomemory can be as difficult to banish as a real one.

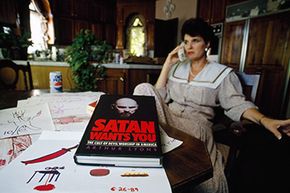

The 1980 book "Michelle Remembers" helped to cement the notion of buried SRA memories in the public mindset. Written by Canadian psychiatrist Lawrence Pazder and his patient (and later wife) Michelle Smith, the book detailed Smith's therapy-aided recall of long-term torture and abuse by a satanic cult in 1950s Vancouver. While eventually discredited, the book provided a basic template for a host of SRA survivor memoirs and was quite a media sensation at the time.

Perhaps you can see the appeal of reclaimed SRA memories. What if the problems you face in your adult life are due to some buried trauma? What if a therapist could extract it from your psyche — drag it out of the darkness and confront it head on? Perhaps you can also imagine a well-meaning therapist's zeal in extracting such a malignant memory, no matter how much of a hand they take in crafting that falsified memory from the cultural script of satanic panic.

And so the headlines ran with accounts of satanic rites and lost memories. Geraldo Rivera's 1988 prime-time special "Exposing Satan's Underground" and other TV exposes paraded a familiar assortment of "expert" therapists, law enforcement veterans and SRA survivors.

The message was clear: The Satanists were out there, intent on ritually abusing and murdering our children in the name of an ancient, evil religion. From the safety of our own sphere of values and beliefs, we could gaze out and blame so much pain on the ultimate — and completely nonexistent — group of outsiders.