Key Takeaways

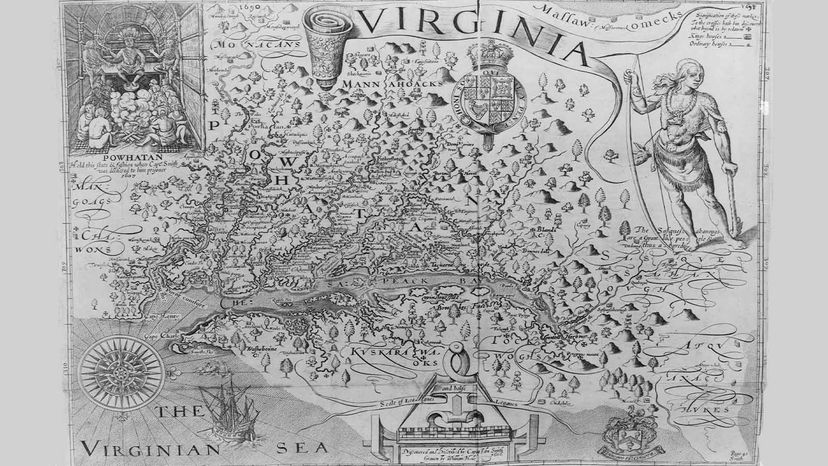

- John Smith's real-life story is more impactful than the fictionalized version, with his significant contributions to early English colonization and the development of the American colonization model.

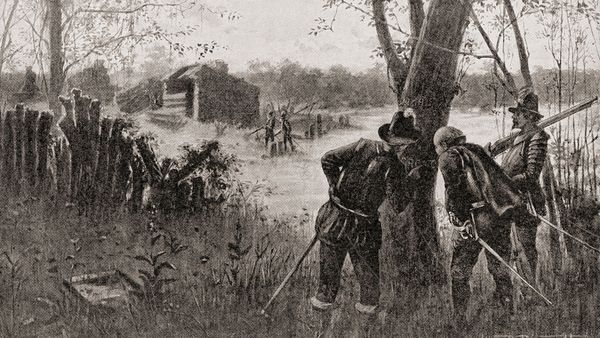

- Born in 1580, Smith embarked on a life of adventure, from fighting in Europe to leading the Virginia Colony, where his cross-cultural awareness and leadership skills were crucial.

- Despite misconceptions about his relationship with Pocahontas, Smith's legacy as a writer, publicist and influential figure in colonial promotion endures, shaping the course of history.

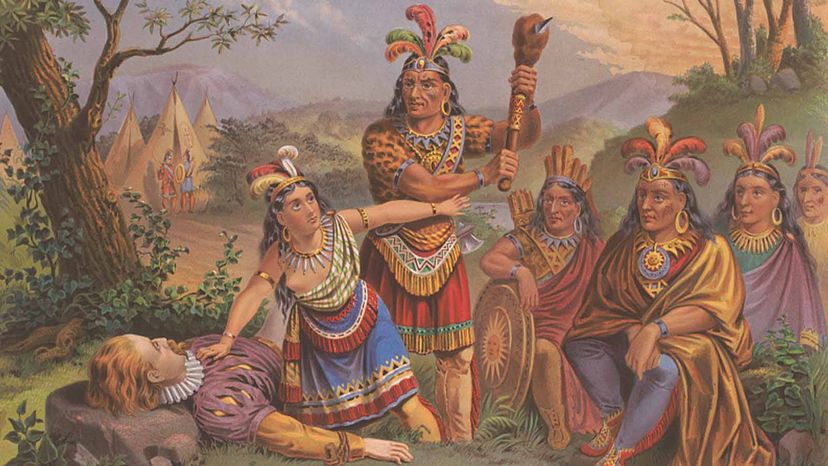

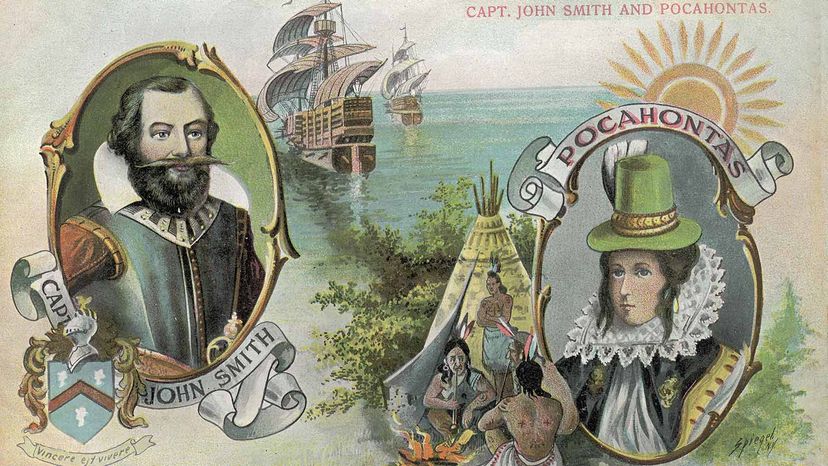

While plenty of people older than age of 8 know that the Pocahontas and John Smith love story is just a myth, and kind of a gross one considering he was 27 when he encountered the 10- or 11-year old girl, Smith's real-life story hasn't gotten much attention outside of academic circles. But the genuine Capt. John Smith had more effect on the trajectory of history than any two-dimensional animated version could ever hope to.

"He was one of the very most important people in early English colonization," says Karen Ordahl Kupperman, Silver professor of history emerita at New York University and editor of "Captain John Smith, A Select Edition of His Writings." "His image has endured for all the wrong reasons." Popular culture seized on the event with Pocahontas, but his interactions with her were the least important among his accomplishments.

Advertisement