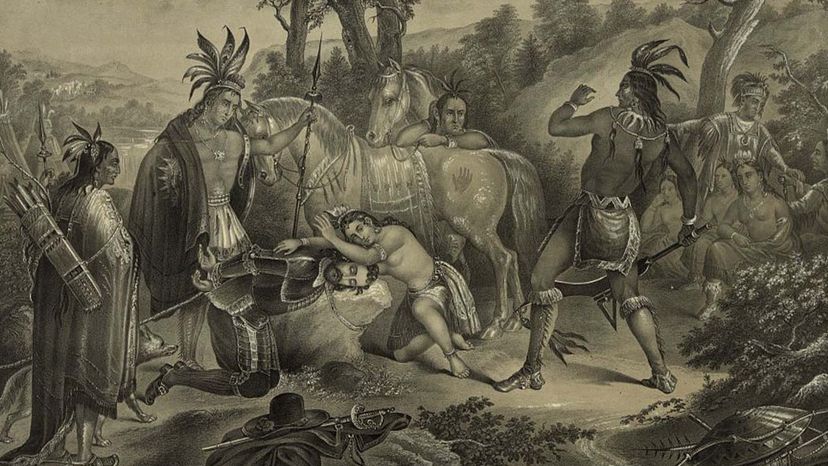

When Disney released the "Pocahontas" film in 1995 and its follow-up "Pocahontas II: Journey to a New World" in 1998, the studio added music and animation to what was already a recognized narrative. The mythical tale of the woman known as Pocahontas included clashing cultures brought to the brink of war, a daring rescue, two love stories and religious conversion, all wrapped up in 90-minute packages with happy endings.

Considering the momentous changes brought by early Native American and European contact, the truth about the real Pocahontas is not only different, it's also significantly more complex.

Advertisement

"The story of Pocahontas is the story of a young woman whose life was coopted by the colonizers to spread the gospel of European civility," says Dr. Darren R. Reid, assistant professor at the school of humanities at Coventry University in England. In brief, Pocahontas can be explained as a young woman who was captured by the English, married to a colonizer and died young far away from home after being placed on display. Or she can be described as a young Algonquin woman who made decisions in her life on her own terms, who chose to convert to Christianity and chose to marry an Englishman and travel to England.

In that sense she is an "empowered indigenous actor," Reid says. Viewing the story of Pocahontas that way reminds us of how important indigenous agency is. "Native Americans were not passive agents in their own history."

What neither of these Disney versions includes is a focus on a love story between Pocahontas and John Smith, first of all because it would have been indecent. So if Pocahontas was not the woman portrayed in the Disney film, who was she?

Advertisement