Visit the Tennessee State Capitol building in Nashville and you'll see two towering statues of former presidents who hailed from the Volunteer State: Andrew Johnson, leaning into a majestic, windswept pose; and Andrew Jackson, tipping his plumed hat atop a rearing steed.

Neither are buried there, but both are so prominently displayed that they've become local landmarks. And they also both overshadow the modest grave of another former president who actually is interred on the grounds: James K. Polk.

Advertisement

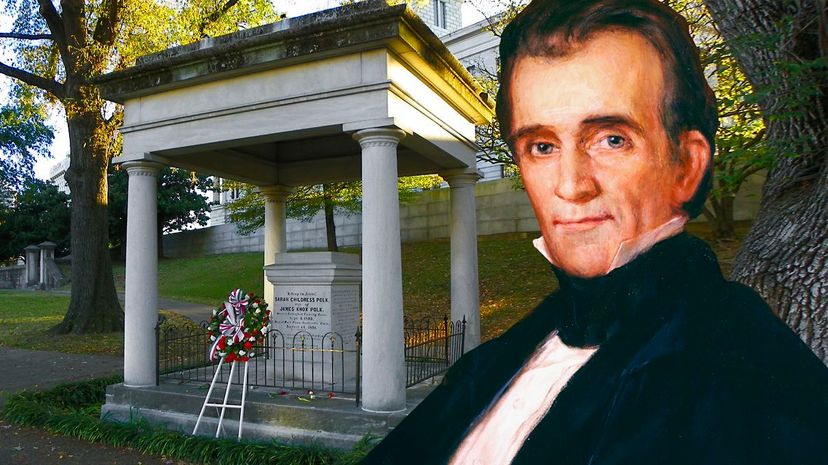

Polk was the United States' 11th president, and along with his wife Sarah, was laid to rest under a small open-air structure on the grounds, and surrounded by a short fence. But the couple may not be there much longer.

There's a movement afoot to exhume the Polks and move them about 50 miles (80 kilometers) away, to the family's ancestral home. Polk was actually born in North Carolina in 1795, but when he was about 10 years old his family moved to the Tennessee frontier, and his father Samuel Polk built a two-story home in the town of Columbia in 1816. The future president lived there for several years as a young adult, and the stately home on a residential street now serves as the James K. Polk Home and Museum.

The thing is, if Polk's body is moved, it won't be for the first time. It'll be for the third.

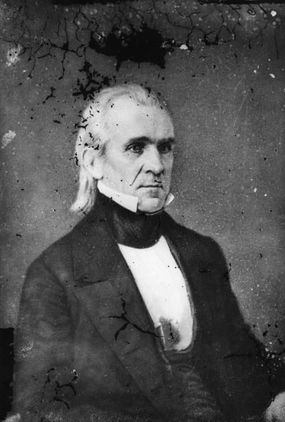

A Lesser-known President

Although Polk had been educated at home, it wasn't until after this surgery — and the improvement of his health — that he attended school. Polk enrolled at a Presbyterian school outside of Murfreesboro, Tennessee, and graduated in two years. Studying law, he passed the bar exam in 1820.

During law school, Polk had clerked for the state senate, and in 1823, was elected to the Tennessee House of Representatives. He was re-elected six times and eventually became speaker of the house, a position from which he championed sitting President Andrew Jackson. His stance earned him the nickname Young Hickory — an homage to Jackson's moniker Old Hickory.

Polk went on to serve as Tennessee's ninth governor, and in 1844 was elected president of the United States. At 49, he was then the youngest president. Instigating the Mexican-American War, Polk was instrumental in the expansion of the United States' territory by more than 800,000 square miles (2,072,000 square kilometers), stretching it all the way to the Pacific Ocean. He re-established the Independent Treasury System, a precursor to today's Federal Reserve System. Polk also created the Naval Academy, signed a law establishing the Smithsonian Institution and oversaw the issuance of the very first United States postal stamp.

Polk had campaigned to be a one-term president, and true to his word, after four years in the White House, he returned to Tennessee.

No Final Resting

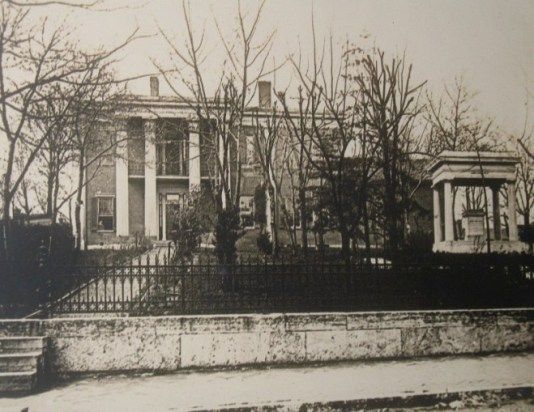

A year later, though, his body was dug up and moved, according to his will, to Polk Place, where it was placed beneath a memorial on the front lawn. Polk's wife Sarah lived at Polk Place for 42 more years until her death. After both Polks had passed, a family squabble over ownership of Polk Place — the president and his wife had no children — sent the former president's plans to remain buried in his own yard awry.

In 1893, Polk's body was exhumed by the state and moved to the Capitol. Following the unresolved family dispute, the state of Tennessee came close to purchasing Polk Place to make it the governor's mansion, but in 1900 a developer bought the property and demolished it.

During the 2017 legislative session, Tennessee State Sen. Joey Hensley sponsored a bill that would move the bodies to Columbia's Polk museum, located in a home that was built by Polk's father. In late March 2017, the measure passed the state senate. It became the first step in creating what Hensley believes is a better burial site.

"I honestly served up here 14 years and had never seen [Polk's grave,]" Hensley told The New York Times in March. "It's not handicap accessible. It's not really talked about much when they do the Capitol tour. Not many people visit it. It's just not a very good place to honor his legacy."

Disinterring the remains of a president also requires the approval of the governor, the state's House of Representatives, a local judge and the Tennessee Historical Commission. About a week after the senate bill passed, the Tennessee Historical Commission came out against the plan to exhume the former president, stating that moving the graves of Polk and his wife would create a false sense of history at the James K. Polk Home and Museum in Columbia. Some of Polk's current living relatives also are against the move, while others are in favor of it. There's even a Twitter account — Polk Journey Home — set up in support of moving his body to Columbia.

If Polk's body is exhumed (again) and reburied (again), there is precedent. In 1858, America's fifth president, James Monroe, was exhumed and relocated from New York to his home state of Virginia. President Abraham Lincoln's body was moved at least 17 times: a presidential record, and all within the confines of Springfield, Illinois. Only time, and politics, will tell if Polk is to be buried a fourth time. If nothing else, his memory lives on through song thanks to the quirky pop group They Might Be Giants:

Advertisement