Key Takeaways

- Viktor Frankl emphasized the importance of striving for a meaningful goal rather than seeking a tensionless state of happiness or comfort.

- Suffering can cease to be suffering when it is imbued with meaning, such as the purpose of a sacrifice.

- The ultimate freedom lies in choosing one's attitude in any circumstance, highlighting the power of personal responsibility and the pursuit of meaning.

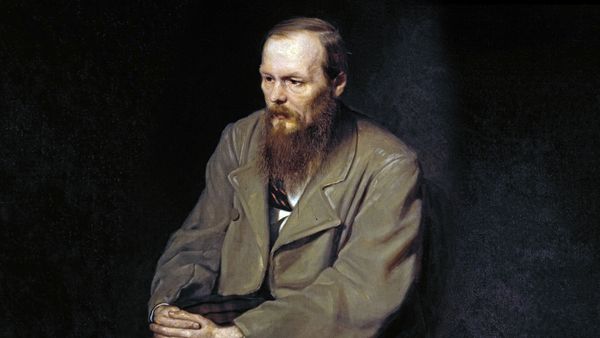

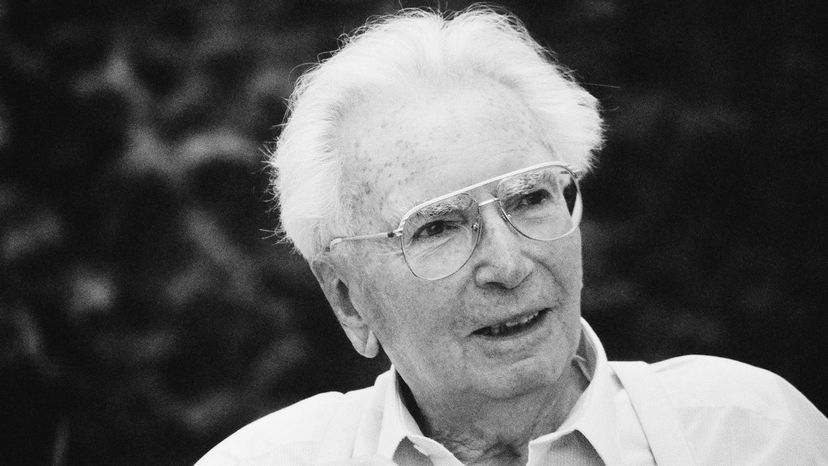

Viktor Frankl was a young and successful Austrian psychiatrist and neurologist when Adolf Hitler and the Nazis invaded Austria in 1938. Frankl was Jewish, and in 1942 he and his family — his pregnant wife Tilly, his parents and his brother — were deported from Vienna to a Nazi-run "ghetto" in Czechoslovakia and then to concentration camps.

Separated from his wife, and stripped of his identity and humanity, Frankl spent three years in four different concentration camps, including Auschwitz, the notorious death camp in Nazi-occupied Poland. He suffered daily degradation, deprivation and violence and witnessed countless friends and fellow prisoners succumb to disease, starvation and despair. Frankl credited his own survival to a method of psychoanalysis that he had begun to develop before his ordeal.

Advertisement

Frankl called his approach logotherapy or "meaning therapy," which centers on the belief that humans can overcome the inherent suffering and disappointments of life by finding meaning and a sense of purpose in every moment. Throughout his intense and prolonged suffering in the camps, Frankl was forced to put his theory to the ultimate test. He credited his survival to grasping tightly to the meaning he found in the love of his wife and the satisfaction of his work.

When the camps were liberated at the end of World War II, Frankl returned to Vienna, where he learned that his entire family, including his beloved Tilly, had been murdered by the Nazis. Inconsolable, he turned again to his work, and in 1946 he anonymously published, in German, "A Psychologist's Experiences in the Concentration Camp," which was later translated to English and republished as "Man's Search for Meaning."

"Man's Search for Meaning" has sold more than 16 million copies in 50 languages and is considered one of the most influential books of the 20th century. We spoke with Alexander Batthyány, director of the Viktor Frankl Institute in Vienna, to discuss five quotes from "Man's Search for Meaning" and other writings that illustrate the power of Frankl's hard-won psychological insights.

Advertisement