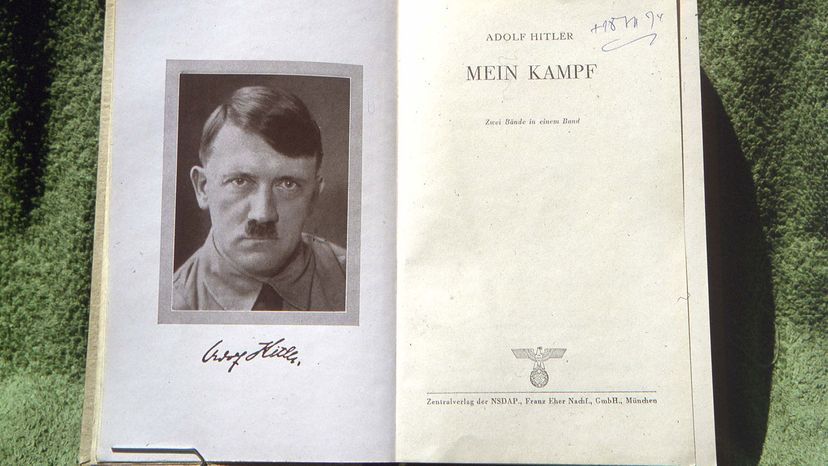

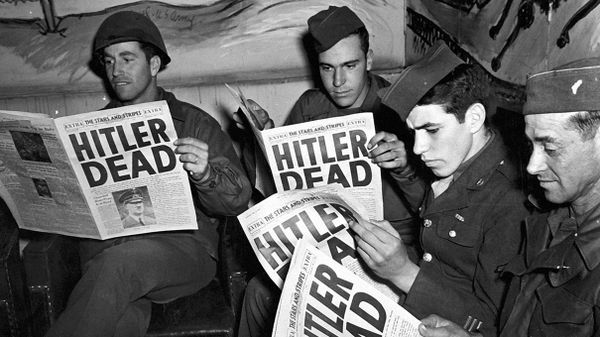

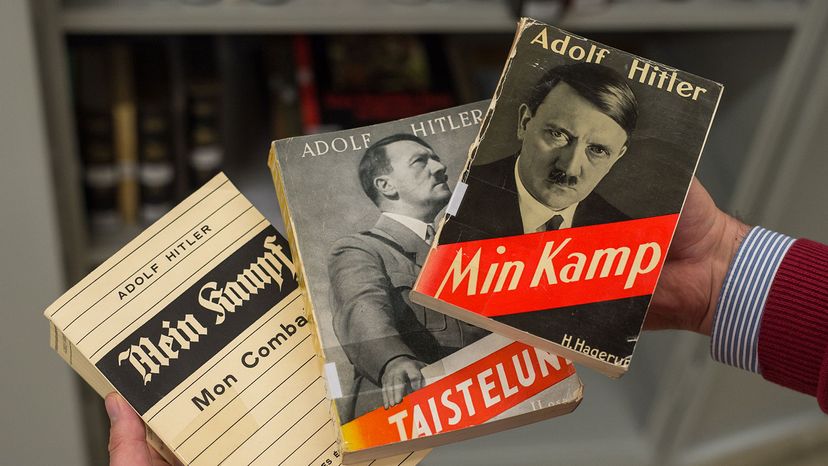

From 1925 to 1945, more than 12 million copies of Adolf Hitler's semi-autobiographical screed "Mein Kampf" (in English, "My Struggle") were sold worldwide and translated into 18 different languages. After World War II, as humanity struggled to process the unthinkable horrors of the Holocaust, Hitler's best-seller was banned from respectable bookshelves and lurked in the popular imagination as the most dangerous and taboo of texts.

In 2016, an annotated critical edition of "Mein Kampf" was reprinted for the first time since the end of the war in Germany on the day that its original copyright expired. Its release triggered heated debate over the merits of reading "Mein Kampf," even in a heavily annotated edition that actively calls out Hitler's lies.

Advertisement

One fierce critic of the book's release, the historian Jeremy Adler from King's College London, wrote that "Absolute evil cannot be edited," echoing the verdict of many scholars and historians that "Mein Kampf" wasn't worth reading for any reason.

"It's not a book that people read, including experts on Nazism," says Michael Bryant, a professor of history and legal studies at Bryant University (no relation) who wrote a book on Nazi war crimes but had never opened "Mein Kampf" before 2016. "There are not that many people who write about it and even fewer people who have actually read the damn thing."

Advertisement