In 1853, Walker was living in Gold Rush-era San Francisco, a magnet for young adventurers looking to strike it rich in the untamed West. By this time, Walker was seriously entertaining his own career as a filibuster. Walker and other would-be invaders set their sites on the northern Mexican state of Sonora, right across the southern U.S. border.

"There was a common belief at the time that the Mexican government wasn't in control of the border territory on their side," says Martelle. "From the filibusters' perspective, it was land for the taking. If they could impose a government, then it would be theirs to defend."

Walker tried diplomacy first, sailing to the Baja Peninsula to request permission for the establishment of a private mining colony in the neighboring state of Sonora. But someone tipped off the Mexican authorities that Walker had grander plans for an American empire in Mexico, and he was kicked out.

Walked sailed back to San Francisco with a new plan. "He would return to Sonora not as a putative settler," writes Martelle in his book, "but as a conqueror."

In San Francisco, Walker and his associates openly recruited men to the cause and equipped a ship called the Arrow with weapons and provisions for a proper invasion. The U.S. authorities caught wind of Walker's plan and seized the Arrow, but in a midnight raid Walker's men were able to steal back some of their supplies and set sail on another vessel, the Caroline, for Mexico.

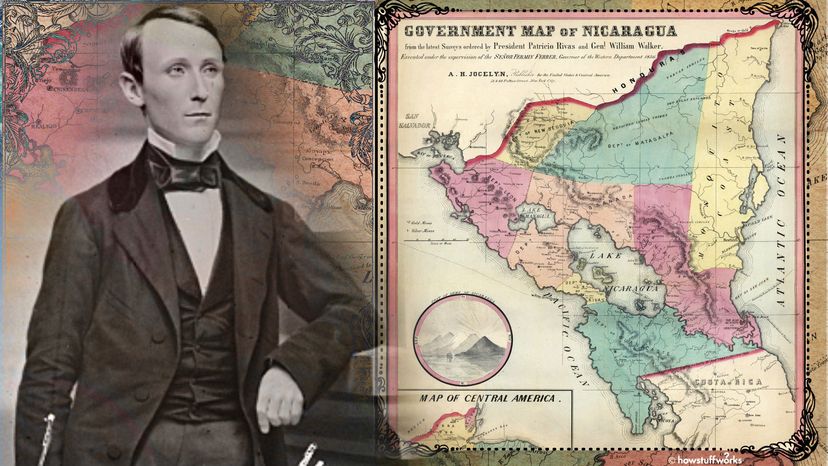

With a ragtag brigade of just 45 men, Walker landed in the port city of La Paz and quickly seized the governor's office, where they lowered the Mexican flag and raised one of Walker's own design for his new country. "The Republic of Lower California is hereby declared free, sovereign and independent, and all allegiance to the Republic of Mexico is forever renounced," Walker declared, giving himself the title of president.

Hundreds of reinforcements sailed down from San Francisco, eager to join Walker's fledgling empire, renamed the Republic of Sonora, and to stake a claim to lucrative mining rights. But once the men arrived, they found an ill-equipped army without a solid game plan. Local ranchers took up arms against Walker's underfed troops, who began deserting in droves.

"Walker had excessive confidence in his ability," says Martelle, and he could be brutal. He shot two of the deserters and ordered that others be flogged. But by the spring of 1854, even Walker realized that the invasion had failed, so he and his exhausted men marched north and surrendered to U.S. authorities at the border.