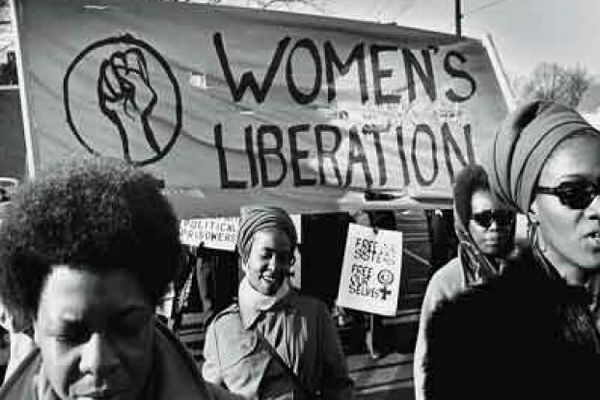

The Greek historian Herodotus traveled extensively throughout the lands surrounding the Mediterranean Sea, documenting their histories and cultures. When he arrived in Egypt in the fifth century B.C., he witnessed some unusual social dynamics. Whereas the Greek women in his homeland were expected to perform household duties and oversee domestic affairs only, Egyptian society permitted far more freedom for females [source: Salisbury]. Women traded agricultural goods in the marketplace while the men wove at home, Herodotus marveled.

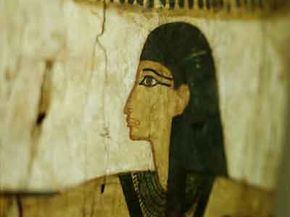

Thanks to smoky-eyed Cleopatra, the notion of liberated, powerful women in ancient Egypt isn't that hard to accept. Even the delicate features of Nefertiti's bust exude an air of authority and confidence. In addition to Herodotus' observations, some Egyptologists have also heralded gender equality in ancient Egyptian culture. Accounts of women receiving the same pay for labor as men, details of legal rights for women and the representation of powerful female deities seem to point to a vaguely feminist culture that valued males and females uniformly. What's more, by the time of Herodotus' visit to Egypt, five women had sat on the throne (Cleopatra shared it with Mark Antony in the 1st century B.C.):

Advertisement

- Nitokret: 2148 - 2144 B.C.

- Sobeknefru: 1787 - 1783 B.C.

- Hatshepsut: 1473 - 1458 B.C.

- Nefertiti: 1336 B.C.

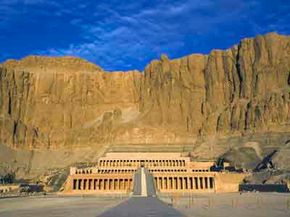

The stories of these women's ascent to power also highlight certain limitations enforced on women in ancient Egypt. More than the others, Hatshepsut abandoned her femininity to fulfill her desire for power. The daughter of Pharaoh Tuthmosis I, became queen after marrying her half-brother, Tuthmosis II. When her husband died following a brief reign, Hatshepsut became the regent of her young nephew Tuthmosis III. Realizing that she had to strike while the metaphorical iron was hot, Hatshepsut adopted male garb and declared herself the new pharaoh. She wore a man's kilt and false beard and took on a new name, Maatkare [source: Kim-Brown]. In return, Hatshepsut left behind a legacy of success during her 20-year rule. She oversaw the construction of the Deir al-Bahri temple, one of the wonders of the ancient world. The female pharaoh also led important trade expeditions into modern-day Somalia, never before accomplished by a woman [source: Kim-Brown].

However, day-to-day Egyptian society didn't reflect this type of literal girl power. Certain areas of Egyptian life were relatively progressive in terms of women's rights, but those allowances existed within an overwhelmingly patriarchal society. Examining the rights of average women reveals that the state of Egyptian affairs might not be as gender flip-flopped as Herodotus conveyed.

Advertisement