Times of war are historically hostile to civil rights. Even U.S. President Abraham Lincoln -- arguably the most beloved president in history -- took liberties with the Constitution during the Civil War. For one, he suspended the writ of habeas corpus to allow prisoners to be held without trial. Historians argue whether this was justified, and even many of his supporters are willing to admit that Lincoln's actions are ethically gray. Eighty years later, another president was faced with a similarly difficult decision when the United States was pulled into war.

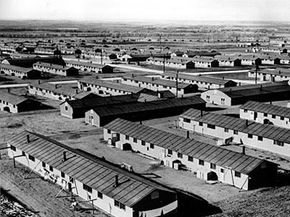

After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt made the decision to relocate more than 100,000 Japanese and Japanese-Americans from their homes on the West Coast to camps around the country. Although FDR himself called them "concentration camps," we don't use that term today -- it's loaded because of its connection to the Holocaust in Nazi Germany. The American camps bore little resemblance to the concentration camps where Nazis were attempting to exterminate the Jewish race, but at the time, Americans knew little about what was really going on inside Nazi concentration camps.

Advertisement

Though many argue that the forced relocation of Japanese and Japanese-Americans was primarily motivated by racism, the U.S. government cited national security reasons for the sweeping relocation (although a congressional commission would later conclude otherwise, as we'll see). Nazi concentration camps were designed to extinguish the Jewish people, who the Nazis considered lesser beings, from the human race. Clearly, the use of the term "concentration camp" to describe U.S. relocation camps is misleading; for that reason, scholars prefer to call them internment camps.

Terminology aside, the relocation of Japanese and Japanese-Americans was a controversial and heavily criticized issue. Not until decades after the war did a congressional commission conclude that the relocation decision was prompted by "race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership" [source: Kops]. So what reasons did officials give in the 1940s for the relocation?

Advertisement