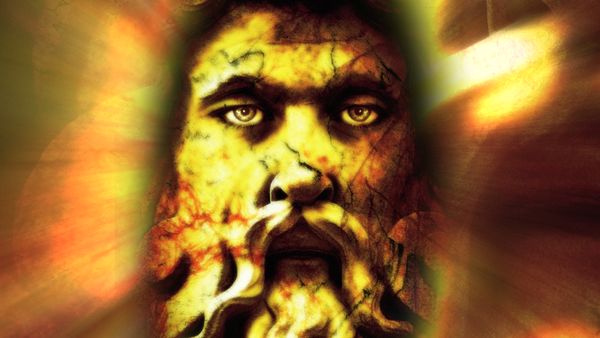

The name "Minotaur" summons the image of a man with the head of a bull, a raging hybrid that often serves as a generic stock creature in games and films.

If this is all you know, however, then you don't truly know the Minotaur.

Advertisement

To understand this creature, sometimes known as Asterion or Asterius, we must confront him where he lives: within the labyrinth of mythology, history and the human psyche.

Before we go further, let's remember the basic myth of the Minotaur, as presented in Hellenic tradition and works such as Ovid's "The Metamorphoses."

The Story of the Minotaur

Once, on the isle of Crete, a king by the name of Minos sought to secure his rule. He prayed to Poseidon for a sacrificial beast he might offer up. But when the sea god sent forth a white bull from the frothing surf, Minos found it too beautiful to sacrifice. Instead, he sacrificed mortal bulls and incurred Poseidon's wrath. The sea god bewitched Minos' wife Pasiphae to fall in love with the Cretan bull, and she soon gave birth to a monstrous hybrid: the Bull of Minos, or the Minotaur.

In A. S. Kline's translation of "The Metamorphoses," Ovid describes the Minotaur as a "strange hybrid creature." And the creature was strange — a "twin form of bull and man" that emerged out of divine wrath and unnatural love. It embodied both shame and sacredness. Minos could only hope to hide – but not kill – the terrifying creature. Thus, Minos employed the master craftsman Daedalus to construct the labyrinth: a tortuous maze that was practically impossible to leave. Here he housed the bellowing Minotaur and fed it the blood of prisoners sent to Crete as tribute by other nations.

Yet all monsters meet their slayer in the end. The Athenian hero Theseus took the place of a tribute sent to Crete, but he befriended Ariadne, the daughter of King Minos. She gave him a ball of string to unwind behind him and details on the twists and turns that would lead him to the strange beast at the labyrinth's heart. There, he slayed the Minotaur and followed the string back to the surface.

That's the gist. Myths, however, emerge from long traditions of multiple tellings. Like the labyrinth itself, the origin of any given myth becomes a twisting, tangled maze that defies easy solution. Just when we think we've emerged from its trappings, we find ourselves – in the words of Ovid – lost to the "windings of alternating paths."

But let's not stand still, lest the Minotaur find us here. Instead, let's first consider the historical significance of the myth.

The Minotaur in History

The story of the Minotaur is intrinsically tied to Crete and the Bronze Age Minoan civilization that thrived there. The early 20th-century British archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans actually coined the term "Minoan civilization" as a reference to the mythical King Minos. As such, myth continues to haunt our modern thoughts of these ancient peoples.

You might assume the Greeks believed Crete to be an evil land, full of brutal kings and profane monsters, but this doesn't seem to be the whole story. According to Nicoletta Momigliano, professor of Aegean Studies at the University of Bristol and author of the forthcoming book "In Search of the Labyrinth: The Cultural Legacy of Minoan Crete," Greek attitudes toward Crete were rather ambivalent.

Momigliano emails that mythological Crete was a "strange and contradictory place," where some treatments of King Minos describe him as a wise, Moses-esque figure, and others depict him as the head of a royal household rife with murder, sacrilege and betrayal.

Of course, this latter vision of Minos lingers in modern culture. It's an example of what academic Joseph Campbell, who wrote extensively about mythology, described as "the figure of the tyrant-monster," an archetype of destructive, egoic disruption.

In reality, Momigliano writes, the exact nature of Minoan rule is much debated – and the political system likely changed over the two-millennia long Minoan Age. Scholarly interpretations include both royal rule and a gender-balanced elite class that might be compared to a council or corporation. King Minos, however, isn't the only element of myth largely missing from the discernible history of Bronze Age Crete. The labyrinth is, too.

"There is no building in Minoan Crete that can be described as a complicated maze (i.e., a complicated system of paths or hedges designed as a puzzle through which one has to find a way)," Momigliano writes. "But the ruins of Minoan palaces, especially the largest one, Knossos, can have a labyrinthine appearance."

Sir Arthur Evans, the excavator of Knossos, equated the structure there with the labyrinth. However, much of Evans' interpretation rests on the linguistic connection between the word "labrys" (double axe) with the prevalence of this motif in the masonry – defining "labyrinth" as the "house of the double axe."

"One should note, however, that the connection between labyrinth and labrys appears to be much more tenuous than Evans suggested," Momigliano writes. "Apart from the linguistic difficulties in relating the two words pointed out by several philologists, one may also observe that, while masons' marks in the shape of a double-axe do appear most frequently at Knossos, they are not exclusive to this site, and other signs are also very common."

What about the Minotaur itself? While no one expects to find literal beast-men amid the Minoan ruins, you might reasonably expect to find images of the creature so associated with the island. Yet, while bulls appear quite frequently in Minoan art – including depictions of humans leaping over the backs of charging bulls – the Minotaur is another story.

"Interestingly and contrastingly, depictions of 'minotaur' images, i.e., of a creature that is half man and half bull, are very rare and relatively late in Minoan Crete," writes Momigliano, "and one may also wonder whether these may be stylized representations of bull leaping, since they appear on tiny seal-stones or seal impressions."

Animal-human hybrid figures factor into multiple traditional and ancient cultures – and Minoan Crete is no exception.

"But there is no prevalence of bulls in these cases," Momigliano writes. "They tend to involve other animals such as birds and goats. So, how exactly one got from Minoan bulls to later Greek representations of the Minotaur is not entirely clear."

The Minotaur in Geomythology

Some writers have proposed that accounts of the Minotaur's subterranean bellowing might have been a way for ancient peoples to explain actual seismic rumblings. This idea is an exercise in what's known as geomythology, a term coined by geologist Dorothy B. Vitaliano in 1968. It is, in essence, the study of alleged references to geological events in mythology. However, this remains an open question, and Momigliano cautions that it gets us no closer to unraveling the mystery of the Minotaur.

"While there are plenty of bulls in Minoan Crete (and earthquakes), Minotaur images are conspicuous by their almost total absence," she writes.

Labyrinth of the Mind

The Minotaur myth likely took many winding, alternating paths to reach its most popular form – and the monster has endured long beyond the empires that birthed it.

"Of course the Minotaur would have had more specific associations for the ancient Greeks (e.g., as an example of punishment for not keeping one's promises to the gods)," Momigliano writes, "But the story of the Minotaur, like many other ancient Greek narratives (and not just Greek narratives) can be and has been endlessly re-imagined to address different aspects of the human condition at different times and in different contexts."

Momigliano's forthcoming book chronicles many of these reinterpretations, ranging from the literary work of André Gide to the paintings of Picasso and various forms of performance art. We just can't seem to get enough of this mythic beast.

For the Minotaur is a collision of the human and the bestial – a perfect symbol of the oft-pondered dual nature of man. He is both victim and tormentor. He is the punisher and yet a punishment himself, imprisoned in what Joseph Campbell dubbed as Minos' "house of death: a labyrinth of cyclopean walls to hide from him his monster."

Sigmund Freud equated the labyrinth of the Minotaur with the darkness of the unconscious mind. For Theseus, it is the monster hidden and pursued. For Minos, it is shame secreted away. And for the Minotaur himself, it is an exercise in cruel and inescapable circumstance. We can easily compare the labyrinth to not only the mind, but also to other complex systems.

Likewise, we can look to many examples of in contemporary horror as further reinteractions of the Minotaur in his labyrinth: Chainsaw-wielding Leatherface in his rural Texas death house, Pennywise the Clown in its sewers or even Jaws in its ocean. They are all terrifying entities made more terrifying by the environment they call home.

In the words of Jorge Luis Borges in "The Book of Imaginary Beings," translated by Andrew Hurley, "Indeed, the image of the Labyrinth and the image of the Minotaur seem to go together: it is fitting that at the center of a monstrous house there should live a monstrous inhabitant."

HowStuffWorks may earn a small commission from affiliate links in this article.

Advertisement