That's when Sherman and his fellow Connecticut delegate Oliver Ellsworth stepped into the fray.

As it happens, the delegates from Connecticut were particularly well suited to strike a compromise between the warring factions. In terms of population, Hall says, Connecticut ranked exactly in the middle. There were six states larger than Connecticut and six states that were smaller.

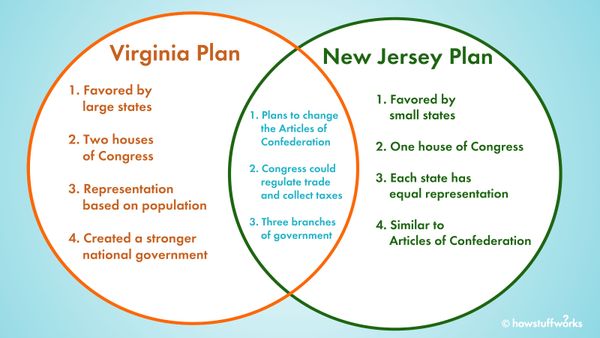

Sherman and Ellsworth proposed a compromise. Let there be two chambers in Congress, just as Madison wanted with the Virginia Plan. But under Sherman and Ellsworth's compromise plan, each chamber would allocate its seats differently. In the House, voting would be proportional, with more populous states getting more seats. In the Senate, voting would be equal, with each state — both big and small — getting the same number of representatives, exactly two seats.

"It was a quintessential compromise," says Hall. "Everyone got something they wanted, but they also had to swallow something they didn't like."

The Connecticut Compromise was sent to the committee to hash out the details, and on July 16, 1787, it was put to a vote. The convention adopted the compromise proposed by a very slim margin of five to four. (Why only nine votes? Of the 13 states, Rhode Island chose not to attend the Constitutional Convention. For this vote, New York and New Hampshire were absent, and the Massachusetts delegates were split, leaving just nine states to make this momentous decision.)

When the Connecticut Compromise was reached, it proved to the delegates at the Constitutional Convention that even the deepest divides could be bridged. Other compromises were then struck about critical issues such as how to apportion House seats and electoral votes in states where slavery was legal. Sherman also played a role in drafting the notorious "three-fifths compromise" that was necessary to secure the Constitution's ratification by southern states.