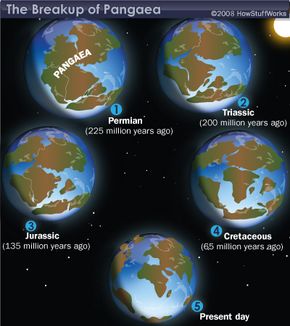

Although scientists agreed with Wegener that there had been a supercontinent, they disliked the reasoning behind continental drift. To really learn what was behind the breakup of Pangaea, they would need to venture all the way to the ocean floor.

From the 1950s to the 1970s, scientists made some important discoveries about the ocean's crust.

Some of the first breakthroughs came in the field of paleomagnetism, as scientists studied the Earth's magnetic fields. The magnetic properties of rocks are classified either as normal, meaning that they have the same polarity as the current magnetic field, or as reversed, meaning that the polarity is opposite the Earth's magnetic field.

This state of polarity becomes locked in when rock is formed. As scientists looked at the patterns of magnetic rock, the layers didn't quite align the way that they were supposed to, suggesting that the magnetized rock and the continents that surrounded it had moved.

What scientists didn't know was why they had moved.

Tectonic Plate Boundaries

The symmetrical striping pattern of the rock provided some more clues, and so did the topography of the ocean's floor. When scientists began mapping the ocean floor, it looked a lot younger than expected.

For something as old as the Earth, scientists expected to see a lot more built-up sediment. They also found oceanic mountain ranges.

Sea Floor Spreading

Paleomagnetic studies revealed that on either side of the mountain ranges, there was a symmetrical magnetic striping. The oceanic map and the magnetic striping were explained in 1962, when a scientist named Harry Hess conceived the idea of seafloor spreading. Seafloor spreading is the process by which magma within the Earth's crust emerges at the mountain ranges and separates the sea floor.

The magma creates a new section of sea floor, which explained why the oceanic crust looked so young: It was continually emerging as a new floor. The newest rock was closest to the mountain range, with older rock located farther away, and each new layer reversed the magnetic polarity, explaining the striping.

When scientists first realized that new ocean floor was regularly emerging, they thought this must mean that the Earth was expanding. But instead, they realized the ocean floor was like a conveyor belt, and that as the new ocean floor emerged, some of the old ocean floor disappeared into oceanic trenches through the process of subduction.

Earthquakes and Volcanic Eruptions

Seismologists were also noticing at about this time that volcanic activity and earthquakes occurred near the spreading ridges and the oceanic trenches. This geological survey evidence suggested that although the continents were moving, the force did not come from the continents themselves, but rather from the ocean's crust.

These moving slabs of earth were dubbed plates, and their movements cause many natural events, including earthquakes, volcanoes and mountain formations. The study of these plate movements came to be known as plate tectonics.

The theory encapsulates both Alfred Wegener's ideas about continental drift and Harry Hess' discoveries about seafloor spreading. Thus, Wegener's ideas about Pangaea were finally explained.